Chapter 1

The alarm bells clanged her awake.

Fire!

Sergeant Jabari leapt to her feet, her hands pulling on her leather jacket and boots automatically.

She rushed out of the barracks, joining a dozen other women awakened by the alarm in the pre-dawn gloom.

Rasha called down from the tower: “It’s over near the Boreas Bath! It looks like just one building still!”

Good. If it was near the bath they’d have plenty of water.

“Rasha, hold the fort!” She turned to the others. “Double-time! Let’s go!”

They ran, each woman carrying buckets or poles.

The streets were largely deserted at this time of the morning, although as they passed the merchant area they could see a few early risers already preparing for the day’s work.

The public bath was just a short distance from there, and as they approached they could see flames shooting from a small, two-story building across the street from it.

“Larima, Georgina, douse the buildings on both sides and make sure it doesn’t spread,” she shouted. “Beth! Roust everyone and get them started with the buckets.”

Georgina, with a long orange braid hanging down her back, sprang into action. She got the bucket brigade up and running, her women rapidly joined by commandeered residents and shopkeepers gawking nearby, and the small pump they had brought shortly began to spray water on the flaming structure. With the fountain so near there was plenty of water available.

So far only the first floor was burning, but the building was made of wood, and the second story was already smoking dangerously. It was only a matter of time before it burst into flame, too.

Jabari tried to look inside to see if there was anyone still alive, but the fire was too intense.

If there was anyone in there, she thought, they’re dead by now. They’ll just have to wait a little longer.

The firefighters concentrated on dousing the adjacent buildings to prevent the fire from spreading—it had already jumped to one building, but fortunately was still small enough to be extinguished quickly.

The second floor suddenly exploded into fire, a puff of flame shooting out of the windows and shattering the few panes that remained. Glass shards rained down, but the heat was so intense the firefighters were safely distant. The fire shot up again with new energy, but that was its last gasp as the water sprays finally began to work. One wall of the building collapsed onto the wreckage, and with a cloud of glowing sparks, the fire was under control.

Embers and tiny flames remained, popping up here and there through the smoke and steam, but now it was just a matter of drenching the mess. By the time the sun rose the fire was dead, and adjacent buildings, though sooty and thoroughly soaked, were largely untouched.

Sipping a cup of cold tea provided by a local shopkeeper, Jabari sat on an upturned bucket, staring at the steaming ruin.

“Everyone says it was a saddlery, shop on the bottom and living upstairs,” said Larima. “No family, apparently—they say she lived alone.”

“It’s not so cold she’d need a fire this early in the morning,” said Jabari. “Brewing tea, perhaps?”

Larima shrugged.

“We’ll be able to look around in a bit. I don’t think there are any embers left now.”

Jabari wound a piece of cloth over her face and rose.

“Let’s go have a look now, shall we?”

Larima followed her into the wreckage.

Most of the second floor and roof had collapsed in the fire, and what wasn’t charred wood was covered with steaming ash. Puddles dotted the floor.

The woman’s body lay in the middle of what must have been the saddlery workshop.

She was dead, of course, and terribly burned, but the axe wedged in her skull made it very clear that it hadn’t been the fire that killed her.

What was even more interesting was the half-charred corpse of a man next to her.

* * *

“OK, so the woman’s body is Mistress de la Corda, just as everyone thought, but that doesn’t help us much,” said Jabari. “We still don’t know who the man was, or how he got into Skala Ereskou.”

“Or why he would want to kill de la Corda,” added Larima.

“Nothing’s turned up in the ashes yet?”

“Not yet. They’re clearing away the debris now.”

“I have to notify the captain, of course. A resident is dead, and somebody else. Almost surely an intruder,” mused Jabari. “He will not be happy with me.”

Larima grinned.

“This is one of the few times I’m happy you’re in charge, not me!”

“Bitch,” grinned Jabari right back. “In any case, though, ask around and find out more about her. And any men in her life.”

Larima nodded.

“Sarge, we’ve got another problem,” came a voice from outside the guardhouse.

It was Georgina. She’d rolled her long orange braid into a bun and pinned it to her head to get it out of the way. Her hands and tunic were dirty with soot.

“We got most of the wreckage cleared and didn’t find anything unusual. It looks like she and the man killed each other and the fire was started by accident; hard to tell for sure. Hard to tell much of anything, actually, but that’s our best guess based on the weapons and wounds. Doesn’t seem to have been any third weapon involved, at least.”

She paused and pulled a small leather pouch from her vest.

“We did find this, though, in the woman’s sash...”

She opened the pouch, and poured the contents out on the flat of her hand.

They looked almost like pearls, iridescent and almost glowing, but with a reddish glint no pearl could match.

“The Honey of the Goddess....” sighed Jabari. “Well, shit.”

She held out her hand.

Georgina rolled the “pearls” back into the bag and handed it over.

“Eight of them, Sarge. Offhand, that’s probably a year’s worth of all our salaries put together.”

“If you can sell them without getting caught, that is.”

Georgina nodded. “If you can sell them without getting caught.”

“So how many people know what’s in this pouch, Georgina?”

“Just the three of us, Sarge.”

“And there were really eight, right?”

“Hey, c’mon... we’ve been through it all together for over ten years. Yeah, Sarge, eight. Really.”

“Larima, how much is in that fund for the three of us now?”

“Not enough yet, Sarge. It’s a good start, but not enough to buy us out, or buy homesteads.”

“So how do the two of you feel about these honeydrops?” asked Jabari, carefully removing three of the “pearls” from the bag, and handing them over to Larima. “You agree we have to report these five honeydrops to the captain?”

“Yes, sir! It’s our duty, sergeant!” said Georgina, standing up straight as if on parade.

“Absolutely, sergeant!” agreed Larima, dropping the honeydrops into an inner pocket in her tunic.

“Constable Georgina, I comment your honesty in reporting this contraband, and hereby authorize a prize money payout of three gold coins.”

“Thank you, sergeant.”

“And I’m off to report this to the captain immediately. Larima, you’re in charge.”

“Sure thing, Sarge!”

Larima waved a casual salute and walked over to lounge in Jabari’s chair. She stretched her feet out.

“My regards to the captain!”

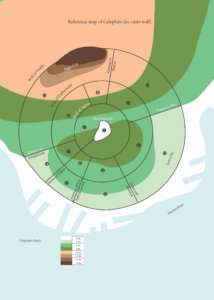

It being a beautiful morning Jabari decided to walk through the Cirque of the Moon, cutting straight through Celephaïs. She used the Aglaea Gate, nodding to the constables there, who were (luckily for them) alert and on duty when she passed.

It was still quite early, and the Cirque was still largely deserted. People were visiting the Estates, as they did every morning whether in respect or prayer, and there was the usual gathering of people around the Hippocrene Spring and the Necklace getting water for the day.

Clean water was available throughout the city, of course: the Slarr River, fed by the mountain springs of Mt. Aran, but many preferred the fresh spring to the flat taste of aqueduct water.

Given a choice she’d prefer fresh spring water, too, but as a Constable she rarely had a choice.

She walked closer to one of the Necklace ponds and scooped up a mouthful.

Cold and delicious, but no time to dawdle.

She continued on around the curving Cirque to the Street of Pillars, which she then followed toward the wharves, and the sea.

The main Constabulary barracks and the captain were located down near the cargo docks, surrounded by warehouses, cargo of all sorts being dragged or wheeled about, laborers shouting and cursing, and the smell of fish, fish, fish. Most of the fish were unloaded on the other side of the Street of Pillars, where the fish market was, but you could never escape the smell.

Jabari once again thanked her gods she was in Skala Eresou... she couldn’t imagine having to live and work in this odor every day. The captain said he was so used to it he never even noticed it anymore, but she found that difficult to believe, much as she trusted the captain.

And since the captain chose to actually live elsewhere—up in High City, in fact—she figured he wasn’t as used to it as he claimed.

“Captain Ragnarsson? Sergeant Jabari, sir, from Skala Eresou.”

The captain was seated in his office, staring at a map of the farmland north of the city.

“Come in, Jabari,” he said, motioning her in. “Apparently there’s a leak in one of the High City cisterns, and the artificers say they’ll need to hook up an alternate from the Slarr Aqueduct for a few weeks so they can fix it. Be a bit of a pain in the neck to run that pipe without damaging the Wall or blocking the outer Boreas Gate.”

He pushed the map to the side and looked up at her.

“And what’s your problem, Sergeant?”

“Murder, and an unknown man in Skala Eresou,” she said, pulling up a bench to sit across from him. She pulled the cloth bag out, and handed it over.

“And this.”

The captain gave her a quizzical look, and opened the bag, rolling a honeydrop out onto his palm.

“Oh, my. More honey. And in Skala Eresou this time!”

“This time?” asked Jabari. “Where else?”

“High City, of course, where the money is. A number of nobles have begun to show signs, and there have been a few, um, incidents.”

“And Skala Eresou abuts High City, through the Wall of Euphrosyne,” mused Jabari. “That’s the lowest side of High City, but still...”

“When did you check that wall last?”

“Twice a year, sir. The last one was about two months ago.”

“Nothing unusual?”

“Not really... a few smaller buildings built up against the wall, but nothing more than one story. The regs only forbid structures on the outside of the walls, not the inside, but I didn’t see anything especially unusual on that side, either. Just the usual gardens and sheds of the smaller estates.”

“Tunnels?”

“We checked both sides thoroughly and couldn’t find anything. The Wall goes down to the rock there, so digging a tunnel would be quite an undertaking to handle in secrecy.”

“Maybe it’s time for a surprise inspection.”

“Yessir, I’ll get on it immediately.”

“Report back to me at once if any new information surfaces. Who’s the man?”

“No idea yet, Captain. I’m looking into it.”

“Damn. Well, keep me informed if you discover anything related to this. Anything at all.”

“Yessir,” she said, rising.

“Oh, Jabari, how many honeydrops were there again?”

“Five, sir. It’s in the report.”

“Oh, so it is. Yes, thank you. Dismissed.”

General outline of Skala Eresou

Chapter 2

“Stop, thief!”

The shopkeeper scuttled around his fruit cart, switch in hand, and shouted after the boy. “Thief!”

Wearing only a ragged dhoti of indeterminate gray, the tow-headed boy stopped walking a few meters down the street, apparently ignoring the angry shopkeeper and instead concentrating on the ripe apple he was so eagerly devouring.

The shopkeeper’s sandals slapped down the paving stones.

“Pay for that apple, boy!” he shouted, reaching out for the boy’s arm with one hand.

“I dropped a coin in the basket, didn’t you see it?” said the boy, smiling as he stepped back to leave the shopkeeper grasping thin air.

The shopkeeper paused confusion.

“You did?”

“Of course I did! Would I be standing here talking to you if I were a thief?”

The shopkeeper thought on that, wiping his brow with a multi-colored towel.

He lowered the switch, tucked the towel away again in his voluminous sleeve, and tightened his sash, which had slipped down over his paunch. While the towel was undyed, his kaftan was covered with a tight geometric pattern in maroon on tan cloth. His kaffiyeh was checkered red, held by a black agal which was in serious danger of slipping off entirely.

“That apple costs a copper!”

“And a copper I paid you, old man. Check for yourself!”

The boy motioned at the street stall.

Seeing the boy waiting there—although still eating the apple—and making no move to flee, the shopkeeper hesitated, then turned and stalked back to his stall. He picked up the little bowl and looked inside.

“There’s no copper in here you little bastard!” he cried, and as he turned to pursue the boy, an apple core hit him in the head.

“Thief!”

The boy vaulted over a nearby cart, turning a somersault in the air, and landed in a roll, which evolved into another leap, this time onto a barrel, and onto the roof of a small shop. He paused, looked back at the furious merchant, and walked to the back of the shop, dropping to the ground and escape.

At a fruit stand nearby an older, elegantly dressed woman nodded to herself, eyes still fixed on that empty rooftop.

* * *

Sergeant Ng and the two constables walked through the market slowly. They were on patrol, but it was a quiet day and they had no place they needed to be. Most of the people there, whether they were merchants, shoppers, or just loitering, ignored them or nodded in greeting; they were more interested in the ones that hurriedly looked away or sidled into the shadows.

They knew every corner of this market, whether it was the vegetable farmers hawking tomatoes and greens fresh from the fields outside the city walls, enormous baskets of grain, or fresh-baked bread and cakes. Local spices were on display in cloth sacks, mouths gaping to reveal seeds and powders in a rainbow of colors and scents. Spices collected here from all the corners of the Dreamlands came to Celephaïs mostly by sea, arriving at the busy docks on the other side of the city, but they all ended up here, joining local herbs and spices that came from the surrounding mountains and forests via the river, or overland. They were quite some ways from the wood market, with its enormous variety of structural or beautiful lumber, transported by river boat, but even so there were a few merchants who had set up shop here, trying to sell cut lumber or exotic woods after being unable to purchase the space they had hoped for in the wood market.

The farm market was the farthest from the docks, and most of the carts brought their goods into the city via the Avenue of the Boreas or the Tanarian Way. Both gates were guarded, of course, but the city was largely at peace and there was little need to inspect anything.

Inside the market, though, it was crowded with buyers and sellers, carts of all types being drawn by a variety of beasts—some dangerous—, street stalls popping up here and there like mushrooms after a rain and blocking the streets, and of course pickpockets. It was a madhouse.

In theory anyone wanting to set up shop here had to get a permit from the Wardmaster, and anyone selling without a permit was to be fined or imprisoned, but the Constabulary had enough to do already and pretty much turned a blind eye when they could. As a result, very few of the farmers selling out of their carts had permits, and if they blocked a street (or the storefront of a permit-holding shopkeeper), the Constabulary could offer excellent motivation for them to move—or else.

The merchants sprayed water over the streets regularly to keep the dust down, but of course that just meant the carts turned everything into a fine layer of slippery mud until the next spray washed it all off again. The odors of spoiling fruit and vegetables, manure from the horses and deinos, and sweaty people combined into a stench that took getting used to.

Not surprisingly, the public fountains here were joined by a selection of alehouses, and the constables went out of their way to be sure the alehouses stayed safe, whether from unruly patrons, theft, or fire. The alehouses reciprocated with drinks to help wash the dust out of their mouths in a generally you-scratch-my-back-and-I’ll-scratch-yours relationship.

There was always turnover as the harvests changed with the seasons and people came and went, but all in all it was pretty stable. As long as they kept crime down to a reasonable level, preventing fires from turning into disasters, and looked the other way when the Wardmaster raised the rent, everything was fine.

There was a fine line between accepting a bribe, which was a sure way to get into serious trouble with the captain, and accepting a drink from an alehouse or a bit of meat or fruit from a merchant. Some constables had a habit of asking for more than usual, others gladly accepted whatever was offered.

As long as it was voluntary and stayed friendly, the sergeant and the captain both turned a blind eye.

Suddenly a paunchy, balding merchant erupted from the crowd and grasped Ng’s arm.

“Constable! A thief! A thief!”

Ng dislodged the man’s sweaty hand.

The merchant was dressed in a tan kaftan with red geometric patterning. Ng sized him up as a mid-level merchant, moderately successful, no doubt with a family shop and perhaps even a hired hand or two.

“Sergeant Ng of the Constabulary. And you are?”

“Thabouti Hamdi of Celephaïs,” replied the other, out of breath. “That boy! He stole an apple from me, and threw it at me!”

“What boy?”

“That boy, over the...” The merchant turned to point, but his hand slowed, drooped. “He’s gone now.”

“A boy? What sort of boy?” asked one of his constables, a woman named Istas. She had a shortsword on her hip and a bow on her back, unlike the third officer, a thin, tall black man armed with a cutlass.

“A boy! Like every other boy!” shouted the merchant, wiping his brow again with the towel. “Filthy, and wearing an equally filthy dhoti.”

“There are lots of boys like that,” said Jay, the black man. “I can see half a dozen right now.”

The merchant mopped his brow again, turning this way and that.

“There! That one! He’s stealing a cake!”

They turned and saw the boy, cake in hand, walking nonchalantly away.

“Halt in the name of the King!” shouted Ng, breaking into a sprint.

Istas followed closely behind, while Jay sprinted off to the side, hoping to cut the boy off.

The boy walked behind a cart of vegetables, and ducked down out of sight... and when Sergeant got there, there was no sign.

The baker walked up and stood waiting while Ng and Istas scanned the plaza.

He was gone.

“That’s Roach,” said the baker. “He showed up a few weeks ago, and isn’t afraid of man or beast. We call him Roach because he can slip into the smallest hole and escape.”

“Where did he come from?”

The baker shrugged. “Who knows? Boys like him come and go. It’s just the cost of doing business,” he said, walking back to his stall, “but it won’t go well for him if I catch him!”

Sergeant Ng nodded to himself.

“So, a barefoot boy, maybe eight or ten years old, straw-colored hair, bare feet... I’ll be looking for you...”

Chapter 3

Later that day, Sergeant Jabari notified the Wardmaster—Mistress Mary, better known as Mary the Boneless because she was paralyzed from the waist down—that they were performing an unannounced and immediate wall inspection.

She acquiesced, of course, since there was really very little she could do about it other than complain to the King, who was quite disinterested and would probably side with the Constabulary in any case... not to mention, the inspection would be long done with by the time she got an audience!

Jabari left two officers at each gate and split the rest of her women into two groups, one working from the Boreas Gate up and then across the Wall of Euphrosyne, the other starting from the di Scalotta Gate to the Wall, until they met somewhere in the middle.

The Wall wasn’t that long, they’d be done soon enough.

She positioned herself up on the Wall itself, in roughly the middle. The walk on top of the Wall was once designed for defense, before the city had grown beyond it, and a third wall had been built even farther out from the Pinnacle. With crenelations and arrow slits it still looked forbidding, but was generally considered more of a hindrance than a defense measure by the populace. There were only gates through the walls, so it could take a considerable amount of time to move on about inside the city.

There were always constables at both ends of the wall where it bordered Skala Eresou, of course, to stop people from entering that way, even though the entire Wall was supposed to be off-limits to everyone but them. From the top she could see both groups of constables at they worked their way along the setback, an empty space running along next to the Wall on the inside to facilitate rapid movement by defenders. Over the years the law had become looser and looser, and now even buildings of one story built up against the wall were pretty much ignored, as long as the roadway stayed wide enough for men and carts to pass easily.

Enforcement was looser, but the law still gave the Constabulary the right to demand entry to every structure abutting the wall. In most cases the owner allowed them immediate access, coming running quickly when called to prevent them from smashing the lock. Or the door.

In a few cases the owner couldn’t be contacted and they’d have some repairs to do later.

Larima pounded on the door of the shack, demanding entry.

“Wake up some of the people around here, and find out who owns this place,” she ordered, and the constables with her spread out and began questioning local residents. Those who could left promptly, discovering urgent business elsewhere, and the laggards confessed that they had no idea who owned it.

It had gone up a few months ago but nobody remembered ever seeing anyone go in or out. Or so they said.

The Constabulary was rarely appreciated, except for theft or fire.

After half an hour or so, with no owner and no information, they broke down the door to discover an empty room with rough boards laid down for a floor.

Larima trusted her instincts and looked underneath... sure enough, there was a tunnel opening hidden under it.

She stepped outside, looked up at the wall walk to catch Jabari’s eye, and motioned.

It only took Jabari a few minutes to climb down the closest ladder and walk over. After one look she dispatched a runner to notify Captain Ragnarsson.

A ladder descended into the pitch-black hole.

“There must be a torch around here somewhere...” Jabari muttered, searching. Ah, there it was, hanging from the ladder.

“Larima, you’re with me,” she ordered, lighting the torch with her flint. “Ihala, make sure everyone finishes checking the rest! And if the Captain shows up, send him down here.”

The torch sputtered a few times then settled down to a steady, almost smokeless flame. No odor, either, she noted. Expensive.

The ladder was longer than she expected, ending about three meters down, with another shaft extending off to the side. One side of the tunnel was the stone of the Wall itself: the horizontal tunnel ran along the wall, not through it as she’d expected.

“I think it’s headed toward the sewage tunnel,” said Larima.

“Oh, shit.”

“Yeah, Sarge. And lots of it.”

They had to hunch over to traverse the shaft, and as Larima had thought it ended up at the sewage tunnel. The shaft opened up in the wall overlooking the flow. The river water was rapid here, picking up speed as it descended the slope toward the sea, but the place stank anyway, of course.

Jabari tied a cloth over her nose and mouth; Larima followed suit.

The stonework of the tunnel was ancient. Celephaïs had stood here for centuries, and while there were tales of its founders and their work, nobody really knew much about its origins, or its tunnels. Some thought they had originally been built as canals—most were certainly wide and deep enough for a small boat, and indeed the artificers often used boats to navigate it for inspections and repairs.

There were rumors of unmapped tunnels branching off into the darkness, and some extending downward where no boat could travel, deep into the earth or out to sea. The artificers had maps, of course, but everyone knew they were incomplete, only covering the portions they actually used.

The blackish, scummy water was about a palm’s width below the walkway at tunnel’s edge. The walkway itself was only barely wide enough to stand, let alone walk on, and was covered with mold and fungi.

Jabari held the torch closer... there were scuffmarks here, in front of the tunnel, but the walkway was untouched a meter or two farther, in both directions.

They must have used a boat, and that meant they couldn’t tell if it came from upstream or down.

She held the torch high and the two of them examined the walls and ceiling. While they couldn’t tell what might be hidden in the darkness, there was nothing visible—no markings, no doors, no signs that anyone had been here for centuries.

“Nothing more we can do here,” she said. “And I’m not getting in that water!”

Larima nodded.

“Let’s go get some air.”

They retraced their footsteps, and Jabari replaced the torch in the holder as they climbed out of the hole.

“I wonder if we can make it look like nobody was here...” she mused. “Larima, what do you think?”

“Uh...” the woman thought for a moment, looking around. “We can straighten up inside easy enough, but we kicked in the door...”

“Yeah, but we kicked in a lot of doors along the Wall, and checked all the structures. Suppose we just put the floorboards back, and make it look like we never noticed the tunnel?” suggested Jabari. “Go get me some dirt, Larima.”

She squatted down and began brushing out their footprints with her hands.

Larima brought in a few handfuls of street dirt, and they scattered it around artistically, camouflaging the few signs of their visit.

“That should do it, Sarge,” said Larima, flicking one last clod onto the floorboards.

“Yup, looks good. Now we need to settle in across the street somewhere to keep an eye on this place...”

They stepped back outside, and Jabari slapped a huge ILLEGAL STRUCTURE sign on the building. Signed by the captain of the Constabulary, it said the structure would be destroyed and the owner fined if it wasn’t removed within a week.

Nobody ever paid any attention to those signs, but it was a good way to explain why they kicked the door in while reassuring whoever used it that they really didn’t care that much.

As they were just finishing up a runner came from the Aglaea Gate. Captain Ragnarsson wanted to come in and requested permission. Even though he was their superior, as a man he couldn’t enter Skala Erasou without the permission of the Council, and since the Council had authorized her in their place, that meant Sergeant Jabari.

“No, I’ll go meet him there,” she said, denying the request. “Larima, finish the inspection, slap a few more notices on some of the more obvious structures, and then pull everybody out. Keep our little discovery as quiet as possible, but bring Ihala up the speed.

“I’m off to fill in the captain.”

“Yessir.”

“And keep an eye out for a good place to wait tonight, too.”

Jabari strode off to meet the captain.

He was not in a good mood.

“Dammit, Jabari, you call me here for a tunnel and then keep me waiting?”

“Sorry, sir. Things are a little more complex than we thought...”

She waved with her hand at a small teashop almost next to the gate, built against the Wall, looking out into the rolling parkland of the innermost Cirque.

“Let me fill you in quietly, sir. This way.”

She took an outside table, pulling it some distance away from the other tables there. The shopkeeper was not impressed, but knew better than to get angry with her, let alone with Captain of the Constabulary.

A pot of spice tea appeared on their table in seconds, and the shopkeeper retreated to safety as soon as he could. She smiled her thanks, but she could tell he wasn’t taken in—her reputation was pretty well established around here.

She filled the captain in, and explained they’d be watching from now on to see who was using the building, if anyone. They still didn’t know if it had anything to do with the murder, but it might explain how the man had gotten into Skala Eresou.

And the honeydrops.

The captain ignored his tea completely.

“You’re coming with me,” he said, after her tale was completed. “We’re off to talk the Chief Artificer.”

“The Chief Artificer?”

“First time?”

“No, but I’m just a sergeant...”

“Yes, but you’re my sergeant,” replied the captain. “Oh, that reminds me... there were some minor errors in your report. I made a few corrections to it, and would appreciate it if you’d rewrite and resubmit. Nothing major.”

He handed over her report with some scribbled edits marked.

“Of course, sir. I’ll have it to you first thing in the morning.”

One of the “corrections” was that the pouch had contained three honeydrops, she noted. Well, we’re all only human, she told herself. Even the captain.

Chapter 4

Roach had established quite a reputation. He’d stolen food from almost everyone, brazenly, sauntering off as if he’d paid and only running at the last minute. Small and agile, he seemed to know every nook and cranny of the market, escaping angry merchants—and Constables—with ease.

He was also a phenomenal shot with small stones—or apple cores—as many merchants and constables had discovered to their regret. While he hadn’t killed anyone yet, he had put out a merchant’s eye with a stone thrown from dozens of meters distant, and had demonstrated an unerring ability to hit people in the center of the forehead hard enough to leave blood and a bump.

Sergeant Ng let his men chase the boy, not expecting any success, while he watched the market from one of the city’s many minarets.

Most of the minarets rose in the Cirque of the Jade Bull, the middle ring. There were more on the higher ground on the north side of the city, but there were other minarets scattered here and there throughout Celephaïs.

One was conveniently located near the middle of the marketplace.

The boy never looked up, not even once, and Ng mapped his hiding places one by one: a culvert; a low rooftop protected by the overhanging eaves of a higher, neighboring building; under the (broken and immobile) cart of a well-known shopkeeper; even, in the early morning, in the stable of one of the inns. He was smart, changing his sleeping place every night, and always checking carefully to be sure one was safe before entering.

His men tried again and again to corner him, and he made fools of the bunch, leaping over them, diving between their legs, dodging and twisting to avoid nets, always with a smile. It may have been a game to him but his constables were getting angry, and he knew it was only a matter of time before they began using their swords or bows on the boy.

The merchants were talking now of raising a complaint to the Captain of the Constabulary. If the Captain got involved because he couldn’t catch a little boy stealing vegetables, he’d probably end up escorting manure shipments somewhere.

Still, if they hadn’t caught the little bastard yet, obviously they needed a new approach, and that’s what he was working on.

After a few days he was confident he knew enough. After stealing a few skewers of meat from one vendor and a loaf of fresh-baked bread from a second, the boy had taken shelter in one of the many entrances to the waterworks running under the city. Most of the entrances to the tunnels carrying the river water used for the scattered fountains and public baths were covered by large flagstones, probably too heavy for that boy to lift, but there was one that had been cracked by age or accident, and was now covered by a simple wood cover.

The tunnel underneath ran in only two directions, upstream and down, and while the boy could certainly traverse it with ease, it was a simple matter to put officers into the tunnels at the next entrances, in both directions. Ng organized the men into two teams, with instructions to block the tunnel in both spots and prepare to capture the boy. They readied nets just in case he could swim as well as he could run and jump.

Little Roach would be trapped.

A few minutes later Sergeant Ng crouched in the shadow of a warehouse, watching the entrance to the boy’s lair from a distance. He waited a few minutes to be sure the rest were in position, then ran to the cover as noisily as possible, shouting “You two, get down inside! We’ve got him trapped now!”

He yanked the cover off, and peered inside.

It was empty, of course, but there was a half-eaten loaf of bread lying there, a few old rags, odds and ends. He used the tip of his boot to see if there was anything else hidden in the rags, but that was all.

Ng listened, and sure enough, he could hear the boy scuttling up the low tunnel, scraping along in his hurry. A grown man would have trouble moving in the tunnel with the water this high, but the boy was making good progress, judging by the sound.

Suddenly he heard shouting, and a yell of pain, and a splash.

More thrashing, muffled voices, then a clear call down the tunnel, voice distorted by the flowing water.

“We’ve got the little bastard, Sarge.”

He pulled himself out of the hole and walked up the street toward the next access, and met them midway. Istas had her hands firmly on the boy’s upper arms, one arm in each hand. She was frog-marching him, steadfastly ignoring his continuing struggles and, at times, lifting him off the ground if his feet refused to move in the right direction. She was dripping wet up to her midriff, and her sandals made a squelching noise as she walked.

The other Constables walked with her, and some distance behind came tall Jay, walking in obvious pain.

“What happened?”

“Nothing important, Sarge... he just knocked me into the water, and kicked Jay where it hurts,” she said, smiling.

“Maybe not important to you but it is to me, Istas,” snarled Jay. “I’ll kill that little sonova bitch.”

Ng chuckled. “Glad to see all that practice in grappling came in handy, Jay. Maybe you can stop by Joy Street tonight and make sure everything still works okay.”

“I’ll have his fucking head on a pike, that’s what I’ll do tonight!”

“Now, now, Jay, he’s just a young boy,” grinned Istas. “Man up!”

She dragged the boy up in front of Ng, who was standing, hands on hips, in the middle of the street. Passers-by and carts automatically swerved around them in hopes of avoiding any interaction... the Constabulary could be awkward at times.

“What’s your name, boy?”

“Roach.”

“Yeah, that’s what they call you, but what’s your name?”

“Don’t have a name,” said the boy, smiling. “Me mom died before she gave me one.”

“How old are you now? Ten?”

“Uncle Sarl said I’s eight.”

“Where’s Uncle Sarl now?”

“Dead. Died the spring.”

“And you’ve been on your own since?”

“Yes. Leave me be.”

Ng laughed. “No, I don’t think we can do that, Roach. You see, you’ve been stealing from the merchants, and they’re quite upset with you.”

“They said if I’s starving to take it!”

“Did they now?” said Ng. “That seems somewhat different from what they told us.”

He leaned down, bringing his face close to the boy’s.

“You know what we do to thieves in this city, boy?” he growled.

The boy head-butted him in the face, and leapt forward, running up Ng’s body and flipping backwards toward Istas, twisting his arms out of her grasp.

He bounced to the ground and took off running...

...or tried to.

Jay was right there waiting, and grabbed him by the neck with one hand.

“Gotcha now, you little bastard!”

The boy struggled, but Jay’s huge hands held him tight, one around his neck and one on his right leg. The more he struggled, the more they tightened, and as Roach began to run out of breath he fell still.

Sergeant Ng picked himself up off the paving stones, face bloody from nosebleed. As least it didn’t seem to be broken.

“Jay, I think you and me are going to have to have a little talk with this roach.”

Jay smiled.

“Oh, yessir, I’ve a few things to say to him myself.”

Ng took some rope from his belt, and tied the boy’s hand together.

“Hold him still,” he ordered Jay, then knelt to hobble his feet. “That should do it.”

He stood, wiped his bloody nose on his arm.

“Now then, maybe let’s take our young guest back to the guardhouse, shall we?”

“Sergeant!”

A woman’s voice came from behind him.

He turned to see an older woman, slim and well-dressed, flanked by two younger women.

“I am Poietria Martine, of Skala Eresou. And you are...?”

“Sergeant Ng, Poietria.”

He was suddenly polite... he had no idea who she was, but any Constable who insulted a Poietria could kiss his chances at promotion goodbye. They had too many connections to the nobility, and the nobility had too many connections to everything.

“What is the boy being held for, Sergeant?”

“He’s a thief, Poietria, among other things.”

“From what I heard right now he is also an orphan.”

“Yes, Poietria, he seems to be.”

“And he is very agile.”

“Yes. And violent.”

“I find it strange that a group of armed Constables had such difficulty restraining a boy so young, Sergeant. Don’t you?”

He gritted his teeth.

“Yes, Poietria. We, uh, were not expecting such a small boy to be quite so violent.”

“Perhaps chasing and threatening him caused him to be violent?”

“Yes, Poietria. Perhaps it did, but he is a thief nonetheless.”

“Boy!” she called to Roach. “If I stand for you, will you stop this nonsense and come with me? I will give you food and shelter.”

The boy cocked his head.

“You are a woman... what would you want with my body?”

Poietria Martine stopped in surprise.

“Your... body...?”

“That’s what you oldies always want, isn’t it?”

She stepped closer and knelt in front of him.

“No, Roach, that is not what I want. I promise no one shall hurt you that way again. There are no men in Skala Eresou.”

“That’s what Uncle Sarl said. Didn’t trust him, either.”

She took one of the boy’s hands in her own. “Maia, come here.”

The older of the two women accompanying her, maybe in her late twenties or so, stepped forward and took Roach’s hand. The other woman, or perhaps a girl in her second twelfth, just stood there watching.

Poietria Martine turned back to the sergeant.

“Sergeant, perhaps I could give the Constabulary a small donation? To pay for your injuries.”

Sergeant Ng scratched his earlobe for a minute.

“You stand for this thief, Poietria?”

“I do.”

“The boy won’t come back to this market anymore?”

“He will not steal here anymore,” she confirmed. “Right, boy?”

He beamed, looking up to her like a guardian angel. “Yes, Poietria!”

A small, heavy bag was exchanged for the boy.

“Cut off those silly ropes, if you please,” she directed. “You can’t eat a proper meal with your hands tied, now can you, boy?”

Ng gestured, and Jay used his dagger to cut the ropes loose.

He waved the dagger under the boy’s nose.

“If we see you around here again, boy...”

Poietria Martine walked away, the two women and her new companion in tow.

“Thank you, Poietria!” called Sergeant, hefting the bag in his hand.

As he left, the boy looked back and signed an insult with his other hand.

Jay took a step forward, hand on cutlass, face red with anger, but Istas moved to block him.

“Leave it, Jay,” she advised. “It’s not worth it for a boy.”

“Jay,” said Sergeant Ng, “I think we could all do with a drink to ward off the afternoon heat, yeah? On me!”

Everyone agreed that sounded like a wonderful idea.

There was an alehouse right up the street.

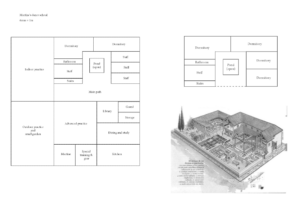

Martine's Studio, with artist's conception of similar Roman home

Chapter 5

Sergeant Jabari walked out into the Cirque of the Moon with the Captain.

Most of it was parkland, with tended gardens, grassy slopes, walkways separate from larger streets for carts. It was scattered with key city buildings—theater, armory, a variety of key storehouses, and of course the Ten Noble Estates. Each of the nine Muses had her own Estate, a stone temple built with stone of exotic colors and textures, fascinating the eye and the mind. They were all different, of course... the earthy agates of Thalia, the black onyx of Melpomene, the soaring crystals of Polyhymnia... they were all beautiful, each in its own way.

Drax was the tenth Noble Estate, though not a Muse... and fittingly, his building was not a temple, but a library, imposing and elegant in the classical Greek tradition.

In the center of the Cirque reared the Pinnacle, a blackish-brown talon of bedrock thrusting upwards toward the stars. With sheer cliffs on most sides, a single switch-backed road ran from its base—at the terminus of the Street of Pillars, running straight to the sea—to the Palace of the Seventy Delights at the apex. Walls and buildings of pink marble were scattered across its surface like cherry petals in the spring breeze.

The Chief Artificer was at a smaller, unassuming building relatively close to the seadocks.

The captain walked in unannounced, scattering lowly clerks and draughtsmen in his wake, directly to the Chief Artificer’s room at the rear.

The door was open; he walked right in.

A large glass window let the sunlight shine into the room, illuminating the shelving covering one entire wall. The shelves were packed with stacks of paper and scrolls, information and drawings of every part of the city and its mechanisms. They were catalogued and maintained, replaced when found to be falling apart, or damaged by mold or water. Rumor had it a duplicate set had been created and was hidden on the Pinnacle.

In spite of the constant care and the catalog, however, the shelves still looked like a rat’s nest.

The Chief Artificer was bent over a table full of detailed plans of the city, deep in conversation with two other men.

“You two, out,” ordered Captain Ragnarsson, hooking his thumb at the door and shutting it behind them after they scurried out. “Artificer Marcus, forgive me. The matter is urgent.”

The artificer, who had stood silent while the other men left, stylus in hand, nodded.

“I gathered so, from your rather abrupt entry,” he said drily. “The cistern?”

“Not directly, but perhaps... Sergeant Jabari here has a short tale to tell.”

He turned to her, and gestured impatiently.

She went through the inspection of the Wall, and the discovery of the tunnel, skipping the fire, murder, and honeydrops entirely.

“How close was the water level to the walkway?” asked Marcus.

“About a palm’s width,” she replied.

“It has to be a swimmer,” he stated, nodding. He walked to the shelving and, without searching or hesitation, pulled out a map.

He rolled it open on the table, plunking weights on the corners to hold it spread wide. It showed the underground waterways for High City and Skala Eresou area.

“These are arched tunnels, which means the ceilings are curved upwards to better support the weight, but during the course of construction the artificers also built in horizontal blocks of stone in many places, specifically here and here,” he explained. “Most of them come down to the height of the walkway. Some have narrow through-holes to allow us to pass, but not these. If by boat, they would have to get into the water and pull the boat underwater, under those stones, before they could proceed. Several times.

“So it really has to be a swimmer, either from some other entrance or up from the sea itself.”

“I’ll need maps of what other access points are possible,” said the captain, picking up the map and beginning to roll it up.

The Chief Artificer grabbed it out of his hands.

“Take your hands off that plan, young man! This does not leave this room, ever!”

He was furious, and even the captain took a step back in shock.

“I will have a copy made for you, showing where the closest access is. Still, if the swimmer is a strong one and knows their way around the tunnels, they could enter anywhere in the city—or even from the ocean—and get there.”

“They couldn’t get in from the Slarr Aqueduct?”

“Impossible. It is fitted with a variety of nets to keep out debris, and is inspected daily. Out of the question.”

“I see...” The captain thought for a moment. “Do you think this could have anything to do with the cistern?”

“With the cistern...?” Marcus scratched his head. “The cistern is well upstream from there, but they are on the same line...I suppose it’s not impossible, but it would take a mighty strong swimmer to swim back upstream to the cistern from there! That’s pretty close to the aqueduct intake, and is a major feeder for a large section of the city. A lot of water goes through there pretty fast.”

“No human swimmer,” mused Ragnarsson. “What about a gnorri?”

“A gnorri?” The Chief Artificer was taken aback for a minute. “There aren’t any gnorri cities near here that I’m aware of, but I suppose a gnorri could swim it easily enough. Or up from the sea. It’d have to be able to stand the sewage, though... there’s not too much coming down from High City there, but the lines run straight through the city to the sea, and they get worse as you go.

“You don’t want to ever go near the downstream end if you can possibly avoid it...”

“You speak from experience, it seems.”

“Oh, yes, I know them well... every young artificer starts at the bottom, and that is the very bottom,” he laughed. “The stench is as bad now as it was when I was cleaning them.”

Captain Ragnarsson nodded, and dutifully smiled.

“When can I expect those maps?”

“The plans will be in your hands tomorrow morning, Captain,” corrected Marcus. “Your office near the sea cargo docks?”

“Yes, thank you.”

After we left the captain asked me quietly, “Why didn’t you mention the murder or the Honey?”

“Didn’t seem relevant,” I said, “and I figured if you thought differently you’d bring it up.”

“Good decision,” he grunted. “Hmm... no way I can join you tonight to keep watch?”

“If you order me I’ll allow it, sir, but I’d really prefer not to... Mary the Boneless is hard enough to get along with now, and she’s already upset with me about the surprise wall inspection.”

“Mary the Boneless... stupid bitch.” He kicked a pebble. “Alright, but I’ll be waiting at the Boreas Gate, and I want a runner immediately if anything happens.”

“Yessir.”

* * *

It was only a short walk from there down to the seadocks, and Captain Ragnarsson decided to pay an old “friend” a visit.

The warehouses were packed quite closely here, usually separated by narrow paths that were usually blocked by carts and people. He knew his way around, though, having spent the better part of a decade on the docks.

And he knew enough to visit this particular alehouse during the day.

If you looked closely enough you could still make out the name on the wall—Rancy Seahorse—and might guess it was an alehouse from the raucous laughter and the stench of thagweed seeping out of the half-open door, but it was clearly not the sort of place a tourist would drop by. Not that there were any tourists here in the dark heart of the docks.

He stepped inside and waited for a second to give his eyes a chance to adjust to the darkness.

There was some light seeping in through the filthy windows up above, and oil lamps scattered about on the tables, making it just possible to see that every face in the room was turned toward him.

Three men near the door stood and began to walk toward him, hands on their weapons.

The largest of the three growled, “Coppers don’t come here with less than a couple dozen men.”

“Maybe you’re in the wrong alehouse, yeah?” chimed in another.

“I’m here to see Captain Rab,” he replied.

“Time to go, copper.”

Captain Ragnarsson held his hands out, empty.

“Tell him Ragnarsson’s here.”

“Let ’im pass,” came a bellow from the back of the room. “If that’s Ragnarsson ya couldn’t stop him anyway, ya little pisses.”

The three stepped back a fraction, allowing the Captain barely enough room to squeeze by, but he didn’t move.

“Get outta the man’s way, dimwit! Ragnarsson’s my guest!”

They stepped back a little more and grudgingly allowed passage, closing in behind him like an escort.

At the back of the alehouse was a broad booth, with an enormous black man sitting in the middle, legs stretched out and leather boots on the table. His bald head and bronze earring glittered in the lamplight, and white teeth shone through the thicket of his beard. He had a liter-sized mug of ale in one hand and a half-naked woman in the other, and nodded when Captain Ragnarsson approached.

“Sit, Cap’n,” he said, pointing, then roared “An ale for the Cap’n, boy!”

The boy came running with a mugful of ale, bowing again and again, and placed it on the table while staying as far from Captain Rab as possible.

Rab picked it up and slammed it down on the tabletop in front of Ragnarsson.

Their mugs clashed against each other, and they drank.

Ragnarson wiped his mouth on his arm and relaxed, letting off a long sigh of contentment.

“Ah, Rab, you know how to treat a constable right, you do. That’s some fine ale.”

“Always happy to show my appreciation for the fine job you do, Ragnarsson.”

Captain Ragnarsson lifted his mug again in thanks and took another slug.

He had known Captain Rab for a long time... they’d grown up together, here on the seadocks, and had crossed paths more than once since. Ragnarsson had entered the Constabulary, and been stationed here for years, while Rabhitandra—Rab—had instead found work as a cargo wrangler. They had both risen through the ranks over the years, one rising to Captain, the other to the unofficial ruler of the seadocks.

Rab knew everybody, and while he never actually broke the law himself he always seemed to have a hand in everything, one way or another. Two, possibly three of the Wardmasters here were Rab’s men. He ruled with a relatively light hand, enforcing peace and honest dealings on the wharves in return for the modest “service fees” he charged.

It was probably illegal, but as long as he kept his fees reasonable and kept the docks operating smoothly—not to mention, as long as he continued to enjoy protection from certain nobles in High City—Captain Ragnarsson was content to leave things untouched.

Informal meetings like this one were invaluable in scratching each other’s back, and they both knew they had more to gain through cooperation than war.

Besides, Ragnarsson thought, at least Rab is honest about what he does, unlike a lot of the people I deal with in High City.

“Mug’s getting a little light, Rab...”

“Boy! More ale! And bring a pitcher!”

Once their mugs were refilled, Captain Rab pushed the woman away, swatting her ass and suggesting she “Go for a little walk, will ’ya?”

The two captains set alone.

“So what’s on ya mind, Ragnarsson? Haven’t seen ya in here for quite a while.”

“We’ve got a little problem and I need a little information, Captain,” he replied. “Have you gotten any reports of gnorri around here?”

“Gnorri?” Rab scratched his beard. “Around here? No, don’t think so. Why?”

“Well, I can’t really go into that, I’m afraid, but I’d, um, appreciate it if you’d look into it, and let me know if any of your people hear anything.”

“They fish in their waters and we in ours, and anyone straying into the other’s waters are dealt with pretty quickly. Usually on a friendly basis, too, unless it’s deliberate. I can’t imagine any of the gnorri from the cities I know venturing out this way.”

“Hmm. I can’t imagine them coming this close to Celephaïs, either, but... things have happened, and I need to check.”

“I can look into it for ya,” said Rab, stretching out his hand.

They shook on it.

“Thank you, Captain Rab. I’ll be sure to appreciate any assistance you can offer.”

“Cree’lo! The Cap’n’s leaving! Walk with him out to the main so everyone understan’s he’s my guest, will ya?”

Cree’lo, one of the three men who had stopped him at the door, grunted and stood waiting.

“Safe voyage, Captain,” said Ragnarsson, draining the mug and slamming it back down on the table.

“Safe voyage, Captain,” replied Rab, raising his mug in a salute and then draining it dry.

The audience was over.

Chapter 6

Poietria Martine and her retinue continued toward the Boreas Gate, one of the three gates to Skala Eresou. As they approached the Avenue of Boreas the shops grew larger and fancier, boasting of their wares to the traffic on the Avenue. While you could find cheaper (and sometimes tastier) food deeper in the marketplace, many people preferred to pay a little more to buy it here and avoid all the mud and noise entirely.

There were three constables on duty at the gate, women dressed in leathers and armed with swords of various types. The foremost woman held up her hand.

“Poietria Martine, you may enter, but who is this lad?”

Martine squeezed his hand.

“Thank you,” she nodded in greeting. “This is Roach and I stand for him.”

“Roach, Poietria?” smiled the constable. “A rather unusual name, I would think.”

“He will have a new one by nightfall, I assure you.”

“You have never brought a male into Skala Eresou before, Poietria Martine.”

“There is a first time for everything,” she smiled. “He is a new student at my school, and I stand for him.”

“You may pass, Poietria Martine,” said the constable, standing back to allow them to walk through the stone arch freely.

The buildings and streets of the Skala Eresou enclave were much the same as the rest of Celephaïs, but Roach felt something was different. He twisted his head to and fro, looking about.

“The public fountain is up ahead on the left,” said Martine. “That big gray building in front of it is the public bath.”

Roach was listening, but he was more interested in trying to figure out what was different... of course! It wasn’t something he could see, it was something missing!

“No men, Mistress...”

“You address me as Poietria.”

He nodded.

“Men are not allowed here, Roach. Boys such as yourself may enter. Skala Eresou is run by women, protected by women, and woe be to any man who tries to enter by force!”

He thought on that.

“Uncle Sarl was a man. He hit me.”

“No man shall you here, Roach,” she reassured him. “But I may if you fail your studies!”

“Studies? You mean, school?”

“Can you read and write?”

“A little,” he said.

She laughed.

“We’ll teach you, boy! We’ll teach you more than that!”

She stopped and looked him straight in the eyes.

“But do you know what we’ll teach you most, boy?”

He shook his head, face expressionless.

“To dance!”

* * *

Poietria Martine’s dance school was in a small, quiet building on the other side of Skala Eresou, close to the di Scalotta Gate. The entrance faced the main plaza there, providing easy access to the public fountain and bath.

They dragged him to the kitchen first, and he had his first full meal in a long time... it wasn’t mealtime and the cooks had their hands full preparing the evening meal, but at a stern look from Poietria Martine they put together a perfect feast for the boy... hot soup, chicken, a heaping bowl of rice with tomatoes and beans, and an apple for dessert. It vanished without a trace as fast as they could dish it out.

When the dishes were empty, Roach stood, without a word of thanks, and asked the Poietria “Now what?”

The head cook, standing nearby eyeing the obvious satisfaction of a handsome, hungry boy in her cooking, tightened her lips, spun on her heel, and stalked off into the depths of the kitchen. Mistress Kileesh had been cook here for decades, and was famous for her silent, disapproving looks. She was also famous for being able to flense flesh with her words when finally provoked to speech.

Martine was also taken aback, but decided to let it ride for now, figuring he was still off-balance after the exciting events of the day.

“Next is a bath and clothing.”

“Don’t need a bath,” he said.

“You need a bath,” she corrected. “Now.”

She turned to Maia.

“Maia, take him to the public bath, then the barber. Here is coin for the barber,” she said, handed over a few small coins. “Find him a clean tunic, and bring him to me when you’re done.”

“Yes, Poietria,” she said, giving a shallow bow, then took Roach’s hand and led him off.

When he returned an hour later, he was a different person... clean, hair cut and brushed, wearing a linen tunic with a Greek meander embroidered around the hems, and leather sandals, he looked the perfect little prince. His face was more handsome than ever, even at his young age.

Martine sighed. He was going to be trouble as he grew into a young man. He already was trouble, she reminded herself.

Roach entered and stood before her silently.

“I’ve watched you in the marketplace toying with the constables,” she said, “Your balance and reflexes are excellent. Your body is still weak and untrained, of course, but you will make a superb dancer. If you can stop stealing.

“We cannot keep calling you Roach, boy. What shall we call you?”

“I like Roach.”

“Rogier, then.”

“If you wish.”

“I wish. You are now Rogier, and will begin training with the first class tomorrow.”

She sat down at her desk again and nodded at Maia, who had stood waiting by door all this time.

“Show him where things are, Maia. You are relieved of your duties for the rest of the day. You are also responsible for Rogier for the rest of the day.”

She kept her face blank as she automatically replied “Yes, Poietria,” and bowed again.

She stepped out of the room, calling “Come with me.” to Rogier as she left.

Maia walked briskly through the school, paying little attention to Rogier and speaking rapidly as if hoping to get it done with as soon as possible.

The school building—there was really only one—had originally been a private estate built like a Roman domus, with a two-story building surrounding the central courtyard, garden, and other structures, but it had been a dance school for centuries, the buildings renovated and repurposed again and again by successive dance masters over the years. The school now consisted of a two-story dormitory for students and staff, a kitchen with adjoining dining room, a small library, and rooms for practice, practice, practice. In addition to an outdoor practice yard (which also featured a small vegetable patch), there was a huge wood-floored practice room, and a smaller exercise room for advanced training.

The students were almost all in their second twefths, and female. He discovered that pre-puberty males could live in Skala Eresou as long as a woman stood for them, but once they reached puberty they would need a special pass from the Council, the women running Skala Eresou. Maia explained he was the only male at the school, and one of the youngest students accepted in recent times.

He thought Maia didn’t like men in general, and judging from the way she avoided approaching him as much as possible, probably feared them.

He listened quietly, taking in everything without comment or question.

It was late afternoon by now, and the students were studying their books. Most sat on the floor, a few lucky ones were seated on one of the benches in the library. They were reading from scrolls and a few books, reciting quietly to themselves.

“What are they doing?” he asked.

“Learning the lines.”

“Lines?”

“The next dance will have both music and speech, and the timing will depend on the speech. They are memorizing the actor’s lines.”

“How can you know what the actor will say?”

“It’s written in the book,” she told him, and pulled a scroll out of one of the shelves. “Here, see?”

She pulled the scroll partially open, revealing tightly packed letters.

Rogier stared at it blankly.

Maia lowered the scroll, looking Rogier in the eyes for perhaps the first time.

“You can’t read, can you?”

He shook his head.

She laughed. “That’s why there aren’t any boys here! Until you came!”

She snapped the scroll tight again and dropped it back into its slot.

* * *

One afternoon, after practice was over for the day and the students could enjoy a little free time before the evening meal, Maia noticed Rogier crouching in the outdoor practice yard, near the herb garden. Curious, she looked closer.

He was motionless, hunched over, head down, staring intently at something.

She squinted to see better... it was a mouse!

It was struggling wildly to escape, trying to leap, and biting at its foot.

She took a step closer to see better.

A bamboo skewer stuck up through the mouse’s leg, impaling it to the ground, and Rogier was just watching its struggles, making no move to free it.

She gasped.

He must have impaled it!

She hated mice, but the thought of deliberately stabbing a living thing like that and just watching it die... she gagged.

Rogier turned and looked at her, face expressionless.

“Me and the cat were mousing,” he said. “Bwada is a good mouser, but I’s even faster.”

Bwada, a huge black-and-white cat that had adopted the school as its home some years before, sat some distance away, watching the mouse.

Rogier and pulled the skewer up out of the ground with one hand, and grasped the mouse by the back of the neck with his other, then abruptly twisted its neck around and casually lobbed the writhing body toward the cat.

He turned to face her.

“What’s for dinner tonight, Maia? I’s hungry!”

Mouth still open in shock, she watched him walk back inside without a word.

* * *

Rogier’s days at the school were not very enjoyable, but even at their worst they were far superior to living on the streets. Ample (sometimes even good) food, safety, soft blankets, even a bath every day if he liked!

Because of his young age he was assigned a personal tutor, in addition to his practice in the first level. Maia was furious with him, because tutoring him meant she lost what little free time she enjoyed.

He mastered the shapes of the letters very quickly, and quickly mastered both block and script. On demand he could write any letter, or all of them, quickly and clearly.

But try as he might he could not read words, and could not write them.

She pointed at the book once more.

“This word. What is the first letter?”

“C.”

“And the second one?”

“A.”

“And the last letter?”

“T.”

“And what does C-A-T spell?”

Rogier was silent. He smiled at her with his best, most innocent smile, but obviously had no idea.

“She ate tea?”

Maia slammed the book back onto the stone wall.

“No! CAT is cat, you idiot.” She jumped to her feet, pacing back and forth in the garden in her fury. “Why can you not see that, you imbecile! I’ve shown you again and again and again and still you can’t read the simplest word!”

“I can write CAT,” he suggested hopefully.

“But you don’t know what it means, do you?”

“No,” he answered, quite satisfied with himself.

He picked up his pen again and began to draw, ignoring her furious pacing.

Minutes passed in silence and Maia approached to see what he was writing... she looked over his shoulder at the sheet of paper in front of him on the ground.

His pen practically flew over the sheet, leaping to the inkpot every so often, then flashing back to the paper where a face was rapidly emerging. As she watched the strands of hair multiplied, growing fuller and blacker, drawn into a braid at the back. The nose grew more evident, and scattering of freckles emerged. Large, slightly tilted eyes opened on the page, staring back into her own.

It was her... he was drawing her face with incredible speed, never hesitating, and never turning to look at her face!

It was done.

Rogier looked at it for a second, judging his work, then nonchalantly crumpled it into a ball and pushed it aside, ready to start on a new picture.

Maia gasped, knelt, reached for that crumpled sheet.

“May I... May I keep this, Rogier?”

He didn’t even look up.

“It’s trash.”

She squatted, gently smoothing out the wrinkles. The ink had smeared a little but every perfection and imperfection of youth and beauty was there, captured in black and white.

She stared into its eyes, entranced, then glanced to see what Rogier was working on now.

It was the face of an angry little man, with a sharp nose, small eyes set deep under bushy brows, receding hairline, sagging cheeks in a face that reeked of too much drink and too few hopes.

“Who is that?”

“Uncle Sarl.”

“Who? You have an uncle?”

“No. He’s dead.”

“But that drawing is so lifelike!”

After a minute he finished the drawing, and crumpled it up like the first.

She gingerly reached out, picking it up to add to her growing collection.

Later, as she was leaving the evening meal, Poietria Martine beckoned her over, ushering her into her room.

“Sit, Maia,” she invited, waving her to a chair. “Show me his drawings.”

She hurried to pull them out of her tunic pocket. There were eleven, in all.

“I didn’t steal them, Poietria! He said they were trash, and I was going to show them to you...”

“Quiet, girl,” hushed Martine. “You did nothing wrong.”

She spread them out of the tabletop, examining them closely. She brought the oil lamp closer to illuminate Maia’s face, comparing it to the drawing.

“I recognize these pictures, of course, of students and staff, but who are these people?”

“He said this one was Uncle Sarl—he said Uncle Sarl was dead—and this one is a constable named Ng, and this one a merchant named Thabouti, uh, Thabouti something, I forget.”

“Enough. Yes, this is Sergeant Ng, I remember. Do you recognize him?”

“Sort of... I didn’t really look at him, to be honest.”

Martine nodded to herself.

“He is very good, isn’t he?”

“Yes, Poietria.”

“You may keep them.” Martine handed them back. “How does his reading and writing progress?”

“Poietria, his letters are beautiful, his script immaculate,” Maia said, “but he cannot spell, he cannot read or write even the simplest word, no matter how I try.”

She hung her head.

“I will try harder, Poietria! I promise!”

“Oh, hush, child. You cannot squeeze water from a stone.”

Martine stood.

“I will take over his tutoring now, Maia. You may return to your normal duties.”

“Thank you, Poietria. I will...”

“You may go now,” interrupted Martine. Waving her hand toward the door.

Maia scurried the doorway, turned to bow once more, and left.

* * *

The first level was mostly girls in their first twelfth, a hodge-podge of different races, colors, styles, even dialects. They all had one thing in common, though: one way or another they had been separated from their families and brought her to dance. They were no longer daughters of farmers or nobles or soldiers, but merely students stumbling through their studies as their bodies matured.

The majority already knew their letters, and could read musical notation; the few who didn’t were learning, goaded on by the staff and the scorn of their fellow students.

Everyone knew Rogier couldn’t read or write, and he became the convenient target of choice. As the youngest, he was also put in charge of cleaning the toilets, and keeping the tank on the roof full of water. Water was drawn from the city pipes, but had to be pumped up to the rooftop manually, drawing a lever back and forth innumerable times until the tank was full. It was tiring, boring work that the students all hated, and they agreed Rogier needed the exercise to build up muscle because he was so small and puny. And because he was the only boy.

Rogier never complained, and never had to be told to do the job... he merely did it every morning, usually before the others woke, and never mentioned it unless asked. The tank was full, the toilets clean, but they all felt cheated that it didn’t seem to bother him.

The morning was full of exercises to build strength, flexibility, and control.

Rogier was stronger than about half of the girls in the first level, and his small stature made it impossible to achieve the leverage they enjoyed with longer limbs, but he easily surpassed all but one of them in flexibility, and surpassed them all in fine control... whether with a finger, a wand, or a thrown rock, he could touch the smallest target the first time, every time, from a standing or a running start.

One night they decided he needed to be taken down a notch, and hatched a plan.

First level students slept on the second floor, in large dormitory style rooms. They were not allowed to leave their rooms at night, except to visit the toilet, and while they could sneak to other rooms, the only ways out were either past the dance teacher whose room was just in front of the stairs—and who was known to be a very light sleeper—or leap over the balcony into the open atrium.

The entire atrium was a large pond with only a small rock or two breaking the surface, and facing it across the encircling hallway were the rooms of other school staff. They all knew the stories of students who had leapt the railing, hoping to leave the school after hours—the front gate was only a few meters from there—but had ended up in the water, or hurt on the stones of the edge, and faced painful punishment from angry teachers.

“Rogier, tonight you must prove yourself to become one of us,” said Tonya, one of the girls in his level. “Go to the kitchen and bring back some fruit for us.”

“What fruit?”

“Oh, any fruit will do,” said Tonya, not expecting him to succeed.

He nodded, and lay down on his blanket again.

They waited to see what he would do, but he merely closed his eyes and waited. As time passed they gradually drifted off to their own sleeping places, whispering that he had given up, or would stupidly try the stairs and be caught.

Later, pitch dark in the silence of the night, he rose and walked to the balcony overlooking the pond. It was invisible in the darkness, no reflections of the moon or stars hidden in the clouded sky.

Without hesitating he grasped the balcony and vaulted over as Tonya watched him from her blanket. She waited to hear the splash, but there was only silence... she threw back her blanket and raced to the edge.

He was gone, but there was still no splash, no noise at all. But he had jumped.

In total darkness.

She waited, and in a few minutes she heard the rustle of clothing below, and suddenly Rogier leapt up from below, grasping the railing with one hand to haul himself up and over.

He held a bag of apples in the other.

She stepped back in disbelief. He placed one apple on the top of the railing, carefully balanced, and handed her the bag.

He walked to his blanket without a word and lay down. The floor where he walked was dry; he had not stepped into the water at all.

As she stood in shock, he flicked a stone from his finger into the apple, and Tonya stared as it tipped, rocked, and finally fell down, down, into the pond with a loud splash.

She was still standing there when the door to the dance teacher’s room opened, and light from the oil lamp clearly illuminated the bag of apples in her hand.

* * *

Poietria Martine considered the girl’s story.

Nobody had ever jumped from the second floor to land on the tiny rocks in the pool before, especially on a pitch-black night with no moon or stars. And while it was not impossible to jump from there back up to grab the railing it would be a difficult leap for a grown man, let alone a boy of ten or less.

Then again, he had already demonstrated the agility of a monkey while making fools of those constables...

The boy had been in his blankets, feet dry, while Tonya had been standing at the railing with the apples.

Had she merely used the stairs and was boasting?

That seemed unlikely... the stairs creaked quite loudly, by intent, and innumerable other students had been heard and caught in the act.

“You are on kitchen duty for two twelves,” she pronounced.

Tonya sighed, head down.

“Yes, Poietria. Thank you, Poietria.”

Kitchen duty meant rising at four every morning to prepare food, then serving and scrubbing after, in addition to all her regular duties and studies. Usually kitchen duty was rotated, with each girl handling it for only one day at a time, two or three times a year, but now she would spend a month in that purgatory.

As they all rose to leave the room, Martine beckoned Rogier.

“Rogier, stay.”

He sat back down on the floor and waited for the room to clear.

When it was empty she walked closer, hands behind her back.

“Did you do it?”

“No, Poietria.”

“I see. Could you leap from the second floor and land on the rocks as she describes?”

“No, Poietria. The rocks are too small. I would fall into the water.”

“You’re sure.”

“Yes, Poietria,” he smiled. “I don’t think anyone could do that.”

“Can you see in the dark, Rogier?”

“No, Poietria.”

“I’m going to blindfold you, Rogier,” she said, picking up a piece of cloth from the table and wrapping it around his eyes. She tied it tight, and checked that it blocked his vision completely.

“I want you to turn around in that spot, three times.”

He turned around three times, feet moving precisely, without losing his balance at all. His arms remained loose at his sides, his chin down in a normal position as he made no effort to try to see.

“Three,” he said.

“Where is the picture of the dragon?”

He pointed diagonally to the right, directly at the picture hanging on the wall.

“Where is the apple from the pond?”

He turned halfway around, and pointed at the apple on the table.

“Take this stone,” she said, “and hit the apple with it.”

He threw the stone with considerable force; she stared at the apple as it rocked back and forth, the stone half-embedded in its flesh.

“Here is a second stone,” she said, handing it to him. “When I tell you I want you to hit the apple with it again.”

She walked over to the apple and moved it half a meter to the right, making sure not to block Rogier’s view, even though he was wearing a blindfold.

“Throw.”

The stone whizzed through the space where the apple had been, clattering off the back wall.

“You moved it,” he said.

“Yes, I did. And you couldn’t tell that I moved it. How did you know where the apple was the first time?”

“I remembered.”

“You remembered where it was, and were able to hit it even after spinning blindfolded!?”

“Yes.”

She sat down, looking at him quizzically.

“You may go, Rogier.”

“May I take the blindfold off?”

“Yes, of course. Go.”

He handed her the blindfold and left silently, not pausing to bow on the way out.

Chapter 7

Sergeant Jabari took another sip of tea. She knew she shouldn’t, that it would just make her bladder hurt even more, but her mouth was so dry she figured it was worth it.

The shack they were hiding in was old and dusty; the slightest movement would raise a cloud to make them cough and their eyes water. They sat there, as still as they could, just watching the Wall and talking sporadically in low voices.

The sky was lightening a little already. Dawn was still an hour off, she guessed, but shortly it would be light enough that residents would begin stirring, and she could go catch a nap. One of the others would take over.

“No luck this time, I guess,” she said.

Larima grunted. She was tired, too, even though she’d come out at midnight to change with one of the other constables. She’d stay here for another four hours until someone replaced her, while Jabari was gone.

Mistress de la Corda was a very dead end so far, and their best hope of getting to the bottom of it was to catch someone going into that building.

Shortly, Rasha entered from the rear, and squatted down next to her, looking out at the Wall through one of the cracks in the shack wall.

“Go get some sleep, Sarge. Me and Larima’ll take it for awhile.”

“Thanks. Gotta pee anyway,” she said, and covered her nose and mouth with a cloth as she rose, surrounded by clouds of dust. “Larima, you’re in charge.”

Outside, she took a deep breath of air, slapped some of the dust off her clothes, and stretched.

The public bath had a toilet, and she headed there first... the bath would be closed this early in the morning, but not the toilet. And then home for some winks.

Around noon she awoke, still a bit fuzzy from lack of sleep but good enough. She headed to the Constabulary barracks to talk to Ragnarsson.

The Captain had stayed by the Skala Eresou gate the first night, hoping for word of a visitor, but only that once. He had other responsibilities, too, and couldn’t spend all his time drinking tea and waiting for her to call.

Either they’d been spotted, or there simply weren’t any visitors.

The Captain was in his office shuffling paper as he was so frequently these days.