Sixteen-year-old Kostubh jerked the rod again, making the float bounce and (he hoped) wiggling the worm enticingly. Gitanshu, three years his elder, stoically watched his own float as if willing it to move.

Nothing moved but the waves, the buzzing insects, and the distant bustle of the harbor.

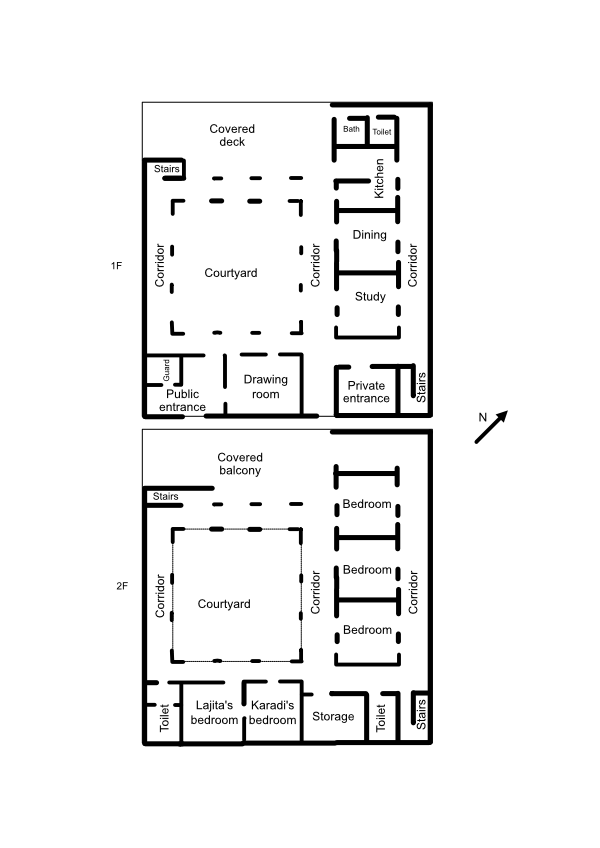

The two boys had snuck out in the early morning, denied a place in the hunting party Karadi had arranged for visiting Lord Prixadius. Dhruv got to go, of course, but he was always with Prixadius. Or Atisha. And since Atisha was waddling around like a fat-assed duck, ready to give birth any day now, everyone was far too busy to worry about the two of them.

A nice day fishing off the rocks opposite Shiroora Shan harbor was much better than all that noise and energy, and constantly being told to do this or fetch that. Dhruv had planned on just going alone, but since Gitanshu’s boss was in Shiroora Shan, quite by accident, he’d arranged to get the day off as well, to “attend the family event.”

They weren’t really interested in catching anything, which was probably why they’d been so surprisingly successful—they’d caught over half a dozen good-sized fish already. They hadn’t brought a creel or net, though, and had just been letting them go again.

Kostubh noticed a movement out of the corner of his eye and glanced up at the top of the Seawall. Two guards were standing there, looking down at them from a dozen meters up.

He waved back, knowing the guards wouldn’t bother them... they came here often, and besides, they were House Chabra.

“You getting hungry?”

“Mmm. You?”

“Yup,” said Gitanshu, lifting the line and hook out of the water. “Let’s head back and get some food.”

“You got any money?”

“Yeah, a little. C’mon, I’ll treat you.”

“I was hoping you’d say that!” laughed Kostubh, standing to reel in his own line. “Curry?”

“Curry.”

They clambered back up the jumbled boulders along the shore to the base of the wall. About three meters high, the wall extended from the base of the Great Seawall for about a kilometer along the shore. In theory nobody was supposed to be down here, and certainly nobody was supposed to leave ropes hanging over the edge of the wall to help them climb back up, but... they were House Chabra.

From there it was a short hike up the flank of The Spine to reach the top of road, which ran from the Narrows at Cappadarnia, across the Great Seawall, and into Shiroora Shan.

“You boys pick up your rope?”

It was one of the guards.

“Yessir, we always do,” replied Gitanshu. “We wanted to inspect the defenses at the water’s edge.”

“No fish this time?”

“We just came to get away from all the excitement.”

“Ah. Lord Prixadius,” snorted the guard. “Yeah, visiting nobility always screws things up, especially when they’re married to a Chabr... Uh, my apologies, Master Gitanshu. When they’re married to someone from House Chabra, I mean.”

Gitanshu waved it away.

“Yeah, whatever. Don’t worry about it. When you’re the third son it’s not that big a deal.”

“Thank you, Master Gitanshu. Master Kostubh.”

He bobbed his head and hurried away, eager to escape before they could change their minds. House Chabra was a pretty good bunch of people, he thought but you never could be sure with nobility.

They took the short way down into Shiroora Shan instead of staying on the wagon road. The Great Seawall was built higher than the docks of the city, and continued into the high hills on the eastern side, the road gradually sloping down to street level. People who didn’t feel like taking the longer, easier way around could just use the stairs.

The Seawall had never been attacked, but the Seagate—the network of chains and logs that could be raised to block ships from passing under the Seawall, or lowered to allow passage—had been used a number of times.

Lajita said it would be needed one day, but she said a lot of things.

Gitanshu led the way to one of the little curry stalls along the wharf and waved a greeting.

“Yo, Hesta! How ya doin’?”

“Master Gitanshu! Hey, good, good,” replied the red-headed cook, probably about the same age as Gitanshu. “And Master Kostubh, haven’t seen you around for a while.”

“Hey, Hesta. Yeah, study study study, and now Prixadius with all his hangers-on. Everybody wants me to do stuff all the time.”

“Well, hungry customers are always welcome here! What’ll it be? The usual?”

“Yeah, two big ones, and hot.”

“Comin’ up!”

Hesta used a huge iron ladle to spoon dollops of thick, light-brown bean curry into two of the waiting bowls, and hand each of them one, then dropped four pieces of hot flatbread on the counter for them to take.

“The tea’s on the table; help yourself,” he added and grinned, revealing misaligned and badly stained teeth.

“Thanks, Hesta,” said Gitanshu, and tossed him a coin. The cook deftly caught it and, nodding his head in thanks, dropped it into his apron.

There were a number of small, rickety table facing the sea, with a scattering of stools and benches around. The boys picked one and got busy tearing bread and scooping up the rich curry.

“Hasta! More flatbread!”

“Yessir, Master Kostubh! Right away!”

True to his word, Hesta arrived very quickly with another four pieces.

“You have to go back tomorrow?”

“Yeah, sorry,” said Gitanshu. “Master Bulbuk’s not a bad guy, but he gets pretty angry when people don’t do what they’re supposed to.”

“You just asked for today off?”

“Hey, my sister’s about ready to pop!” laughed Gitanshu. “We’re already here; that’s the least he could do, right?”

“I guess,” said Kostubh, pouring more tea and waving the pot so Hesta could see they needed more. “I’m stuck here learning shit and you’re on a damn caravan to Despina!”

“And from there to Rinar by ship!” boasted Gitanshu. “Master Bulbuk says we’re going to Celephaïs next spring. Celephaïs!”

Kostubh scowled.

“Yeah, lucky you.”

“Papa sent me off to learn from Bulbuk two years ago, when I was seventeen... you’re almost that now. Ask him; maybe he’ll let you come, too.”

“Damn! You think so!?”

Gitashu shrugged.

“Can’t hurt to ask.”

“Wow, Despina and Rinar! I’ll ask him tonight.

“About two months, right?”

“Yeah, unless something unusual happens. Master Bulbuk says he doesn’t expect anything this trip. He says the weather’s been good, and piracy is down along the Cuppar-Nombo coast.

“If Master Bulbuk says it’s OK with him, I bet papa would go along.”

Kostubh used to last of the flatbread to wipe his bowl clean of curry and crammed it into his mouth. He sloshed another cup of tea and drank it down, then stood and stretched.

“You done yet?”

“What, you’re gonna run and ask him now? Can’t wait?”

“C’mon, Gitanshu! Let’s go!”

Gitanshu laughed and drank down the rest of his tea.

“Thanks, Hesta! Good as always!”

“Come back soon, Master Gitanshu, Master Kostubh!”

They ignored him and began walking toward the stairs up to the Chabra main house.

“You really think papa’ll let me?”

“You’re sixteen,” said Gitanshu. “He’s gonna let you go one of these days; might as well be today.”

They found Karadi looking out over the bustling port and the Night Ocean.

“Well, well... if it isn’t the two absent uncles!” he chuckled. “I hope you’ve already dropped by to see your new nephew and congratulate Prixadius and your sister?”

“Of course, papa, we were just on our way there now, but happened to see you standing here,” countered Gitanshu quickly. “Kostubh has something he wants to ask you.”

He pushed his younger brother forward and deliberately looked up at the clouds.

There was a moment of silence, broken by Karadi: “Yes?”

Kostubh inhaled, straightened his shoulders, and looked his father in the eye.

“If Master Bulbuk agrees, I would like to accompany Gitanshu on this trip. They’re going via Eudoxia, Thace, and Despina to Rinar. I promise to follow his orders, and I’ll work with the crew. I know I’m only—”

Karadi held up his hand, cutting off the torrent of words.

“Kostubh, once you’ve started on this venture you can’t suddenly change your mind, you know. You would have to stay with his caravan until he returns here, which will be at least six months from now, or until he releases you.

“And I can say with confidence that he will not release you without my permission.

“Are you prepared to follow Master Bulbuk’s orders for half a year, without complaint or any special treatment? You’d be an untrained recruit, at the bottom of the crew.”

“Yessir, I am,” he shot back without a moment’s hesitation.

Karadi grinned and stepped forward to hug the lad.

“I’d be happy to let you go if that’s what you want. And I’ll even ask Than Bulbuk to take you, but that’s all I can do.”

He turned to Gitanshu.

“Kostubh will make mistakes, just like you did. It’ll be your job as one of Than’s team to make sure he learns from them. But as Kostubh’s brother, try to make sure he doesn’t kill himself.”

“Yeah, I’d already realized what I’m getting myself into,” grumbled Gitanshu, face sour. “I’ll try, but Kostubh does some pretty damn stupid things at times.”

“It runs in the family,” snickered Kostubh. “We all take after papa.”

“If you only knew,” laughed Karadi, and gathered the two boys closer, an arm around each. “I think it’s time to introduce you to your nephew, and maybe we can tell your mother about all this a little later, what do you say?”

* * *

Than Bulbuk of Eudoxia had arranged for transport on one of the many ships plying the western reaches of the Night Ocean. Now that piracy was almost unheard of, especially in the northern waters closer to Shiroora Shan, more and more trade between Eudoxia, Adelma, and Shiroora Shan was moving by sea, and traffic along the older caravan routes along the coast had plunged dramatically.

He knew many of the ship captains, of course, as his route had passed through the Night Ocean for decades, and he had no difficulty finding one he knew and trusted for this part of the journey.

The ship’s crew took care of the ship, but Kostubh and the rest of Than Bulbuk’s people had to do most of the heavy labor involved in getting the cargo into the hold and secured properly. The crew was happy to offer advice and assist, but always seemed to have more pressing jobs when it came to hoisting or carrying crates.

Kostubh, of course, was expected to be helping.

“Kostubh! Quit gawpin’ and help get the goods movin’, boy!”

“Yessir!” he shouted to the caravan’s loadmaster, a middle-aged Shang man named Chang Wu. Kostubh didn’t know much about him yet... in fact, he didn’t know much about anyone in the caravan yet.

He ran down the deck to the cargo hatch, already open, and glanced around to see what he should be doing. The ship’s crew was operating an overhead pulley, moving various crates, bundles of textiles, and huge jars of wine from the wharf to the hold, while Than Bulbuk’s people were responsible for securing them there in good order.

Kostubh figured he could be of most use standing between the pulley operator and the open hold, relaying information and making sure everything went smoothly.

“Another thirty or forty centimeters up,” he ordered the pulley operator, gesturing with his hand. “The ropes are getting all tangled on the floor.”

“Get out of the way!” shouted the woman on the pulley. “Can’t see anything with you blocking me!”

“Hey, don’t tell me what to—”

“Kostubh! Get your ass down in that hold and get the damn cargo loaded!” came the shout from Chang Wu. “And shut your damn mouth!”

He spun around, on the verge of shouting back with all the anger of an insulted Chabra boy, but noticed Gitanshu standing on the wharf, helping unload the cargo as it was transferred over. His older brother didn’t say a word, but he caught Kostubh’s eye and shook his head “No.”

Kostubh clenched his jaw and glared at Chang Wu for a moment, then jumped down into the hold.

“Well, well, if it isn’t the new kid,” said Ran, an enormous, blond-haired youth who was the unspoken boss of the hired laborers. “Help get those crates over here.”

Kostubh froze for an instant, still angry at the tongue-lashing from Chang Wu a moment earlier, but even that momentary pause was too long for Ran.

His ham-sized fist shot out, slamming into Kostubh’s chest near his shoulder and knocking him backwards. He barely managed to catch himself on a bale of Zeenar cotton.

“You struck—”

Ran grabbed him by his tunic, yanking back onto his feet again.

“You get over there and start helping or I’ll break your head in,” he said, and pushed him toward the pile of crates.

Kostubh took a quick look around. Everybody was still moving cargo, but their eyes were all watching him. And none of them looked like they wanted to get involved.

He was pretty good at fighting—Karadi had made sure that all his children knew how to fight—but Ran was very big, and Gitanshu had just told him to shut up.

Kostubh shut up and turned to help.

Another man was slowly shifting a heavy-looking crate toward the stern, and Kostubh took the other side, working with him to nudge it forward.

As his eyes adjusted to the relative dimness of the hold he recognized the characters inked down the side.

“Hey, this is crystal from Shiroora Shan!”

“Yeah, it is,” said the other under his breath.

“And if you break it Ran’ll take it outta your hide,” he continued after an unusually long pause. “If there’s any left after Chang gets through with you.

“You’re new, right? From Shiroora Shan?”

“Yeah. Uh, Kostubh of Shiroora Shan.”

“Robert of Zeenar.”

“You’re a pretty quiet guy, Robert.”

“I... I don’t make friends easily.”

“Hey, I’ll be your friend. First person that’s talked to me since I climbed onboard!

“I’ve been to Zeenar a couple times,” said Kostubh. “Usually just to Karida with my father, sometimes to Zeenar, once as far as Ebnon.”

“All the way to Ebnon!? Never been down that way... I hear it’s all swamp and leeches.”

“Nah, the Boorsh Fens are a pretty long ways from there,” chuckled Kostubh. “Never been there myself, but there’s no swamp around Ebnon, except maybe in the spring when the Tlun floods.”

“Yeah, we get runoff from the mountains in the spring, but rarely any flooding... the larger rivers are some ways away.

“Love the way the streets turn into canals in Karida, though! You been there in the spring?”

“Only once,” said Kostubh, shaking his head. “Pretty neat, huh?”

Robert laughed.

An hour later they were all done, and joined the rest of the caravan on the deck.

The ship set sail shortly thereafter. Kostubh and the others had little to do until they reached port in two days except eat, sleep, and gamble. People who had joined the caravan in Shiroora Shan hadn’t been paid yet, but since they would be paid when they reached Eudoxia they were able to gamble with promises, usually written ones.

Gitanshu was busy with Than Bulbuk most of the time, leaving Kostubh to fend for himself, and he quickly became a fixture in the various gambling schemes under way. He didn’t actually cheat, at least not that anyone ever saw, but somehow he kept winning more than seemed reasonable.

Ran, the big blond man who had been running the gambling operation since the caravan left Karida, quickly recognized Kostubh as a threat to his own success, and often dice or cards ended up with the two of them in a face-off. It never came to blows—not quite—but it was pretty clear that it would someday. And Ran was taller and heavier than Kostubh, by a significant margin.

Kostubh was pretty good at gambling, and knew an opportunity when he saw one. He gradually built up a coterie, loaning them money, paying off their gambling debts, or just defending them from Ran. Robert in particular was deep in debt to Ran, and Kostubh went out of his way to help him recoup his losses and then some.

The morning of the second day they docked at Eudoxia.

The port was enormous, and far, far older than Shiroora Shan’s recent growth. Eudoxia had been a major trading city on the Night Ocean for centuries while Shiroora Shan was still a tiny fishing village, and it showed.

The wharves were much larger than those of Kostubh’s home city, and the walls and minarets of Eudoxia dwarfed Shiroora Shan’s. More than the bustling wharf and the towering defenses, though, Kostubh was astonished at the sheer number of people... he’d thought the streets of Shiroora Shan were crowded, but this...! He’d never imagined so many people in one place!

They all spent the afternoon unloading all the crates and barrels and other cargo from the hold, and getting it moved to the wharf safely.

Than Bulbuk had arranged teams from his own warehouse to handle transport. A line of deino-drawn wagons stood along the wharf next to the ship waiting patiently for cargo to be loaded up. They were all marked with Than Bulbuk’s yellow ox-head symbol.

They’d unloaded the ship’s cargo onto wood platforms standing along the wharf, built to about the same height as the wagon beds, and thanks to rollers on the platform and in the wagons, it was fairly quick and simple to move everything.

The last wagon rolled out in less than half an hour.

Kostubh walked, of course, with the rest of the workers.

Gitanshu and a few other managing the caravan had gone on ahead, so Kostubh just followed everyone else, listening and learning.

He already knew a few names and faces, but there were about a dozen workers, men and women, most a little older than he. Most of them had been hired for one portion of the trip, usually to the next city on the route but sometimes longer distances. They’d all be paid off here in Eudoxia. Workers who had done well would be offered the same job on the next portion, probably through Thace to Despina. Workers who did exceptionally well might even be offered an apprenticeship: the first step to a career, and what most of the workers were hoping for.

Kostubh had little interest in becoming an apprentice trader... he was a Chabra, after all, and House Chabra already controlled much of the lucrative trade around the Night Ocean.

Suddenly someone grabbed his shoulder and spun him around.

Ran.

“Hey, new boy! I see you slacking off again and I’ll beat you even sillier.”

Kostubh yanked his arm free and took a step backwards, opening up a little space between them.

He flexed his fingers, tensed his shoulders, and then lifted his fists to the fighting position.

“I’m not good at taking orders,” he spat, and glared at the larger man.

“Don’t fuck with me, boy!” snarled Ran, striking forward with a massive fist that smashed through Kostubh’s defenses and into his abdomen.

He staggered backwards in agony, but before he even had time to fall a second blow shot home into the side of his head and he collapsed onto the nearby wall.

Ran picked him up by his tunic and dragged his face up close.

“You hear me, boy?”

Groggy, Kostubh just tried to stop his head from spinning.

“I said, You hear me, boy?” repeated Ran, shaking Kostubh like a terrier with a rat.

“Yeah... Got it,” he whispered.

The hand let go and he dropped to all fours on the cobblestones.

As he caught his breath he watched the rest of them walk on.

Robert stayed behind, and helped him to his feet.

“You OK?”

“Yeah, I guess... thanks.”

“Don’t get in his way. He’s pulped a few of us already.”

Kostubh started to chuckle, then winced.

“I won’t... not again.”

They walked after the others, Kostubh still a little wobbly on his feet.

“So how come you’re working for Bulbuk?”

Kostubh shrugged.

“The usual... got tired of living at home. Time to go see the world!”

“Yeah, me too. Got tired of getting beat on by my old man.”

“So now you get beat up by Ran? That’s an improvement?”

“I don’t think Ran’ll be with us after Eudoxia. He’s got the muscles of an ox, but also the brains.”

Kostubh snorted.

“You going on after Eudoxia, Robert?”

“I hope so! I’ve been here for two years now, shouldn’t be any problem... might even get apprenticeship!”

“That fast? Thought it took longer.”

“Usually does, yeah. Hey, I can dream, right?

“What’re you signed up for?”

Kostubh hesitated. If he revealed he wasn’t a hired worker he’d probably be ostracized, and that’d make life pretty miserable. But it’d be strange to say he’d already been hired through Rinar. He was a new worker, after all, and it’d be unheard of to hire an unknown worker that far.

“Despina,” he said, picking the end of the coming land route as a good end-point. “The voyage from Shiroora Shan to here doesn’t count, after all.”

“You’ll like Despina,” said Robert. “Bulbuk went there last year, too.”

“Never been there.”

“Most of the buildings are white-washed brick, real thick walls to keep the heat out. Beautiful when the morning sun hits it, all pink and orange.”

“So what’s there besides white-washed houses?”

Robert shrugged.

“Nothing except trade routes, as far as I know. Rinar’s a hell of lot bigger when it comes to trade, but almost everything moving between the Night Ocean and the rest of the Dreamlands goes through there. The Cuppar-Nombo route doesn’t have enough oases along the way, and nobody cuts through the jungles between Dothur and Eudoxia.”

“You been to Dothur?”

“Nah. You?”

“Nope. Never been west of Eudoxia.”

“I’m not much on jungles,” mused Robert. “The steppes are best, green everywhere. Deserts are OK, I guess, but not by choice. And jungles? Uh-uh, no way.”

“No jungles up around Shiroora-Shan, just mountains and the Night Ocean, with the city squeezed in between."

"Well, we'll see some of the jungle on the way to Thace,” said Robert. “Hopefully from a distance, though.”

Kostubh glanced ahead to see the rest of the work crew standing in front of a white-walled compound. The yellow ox-head standard was flying over the gate.

Than Bulbuk’s home base.

Just as they joined the rest of the group, Loadmaster Chang Wu came walking out of the gate.

“Follow me to the wagons. Items with a red circle on them are unloaded here, and need to be moved into the warehouse. The warehouse team will show you where they go.

“Everything else has to be transferred to desert wagons.

“And it all has to be done carefully, you clods!”

“Yessir,” came the chorus of grumbles, and they moved as a group toward the wagons and the waiting warehouse.

A few hours later they were done—nobody had dropped anything—and Chang Wu stepped on onto a wagon to speak.

“OK, you can use that barracks over there,” he pointed, “and you can get a meal there. I’ll be by later to settle up payments, and arrange for the next leg of the journey.

“It’ll take a day or two before we’re ready to go, but as you know we’ll be traveling on to Despina mostly on camelback, with at least two, possibly three horse-drawn wagons. We’ll be using the Trade Road, of course, so unless we run into a sandstorm or something it should be a pretty quiet trip.”

The Trade Road—a whole network of roads, actually—ran from Eudoxia to Thace, then on to Despina and Dothur. The ancient stone-paved roadways had been built in the unknown past, and marked with time-weathered statues every few kilometers. The sands had worn away the statues until it was impossible to tell exactly what they had been, but people said they were lizardfolk, and the stumps of tails still remaining suggested the rumors were right.

Desert storms shifting dunes often buried the roads themselves, but usually the statues were tall enough to serve as landmarks. Unfortunately, sometimes the shifting sands also revealed new, unknown statues marking roads that led to where no-one knew. Other rumors told of caravans that had mistakenly taken the wrong roads, trusting the silent statues to show the way, and vanished forever.

Kostubh was familiar with them, of course, as they also ran from Adelma north to Nurl, and forbidden Irem.

The Ibizim were masters of the desert road network, and often served as guides for travelers on the Trade Road.

They made their way to the barracks. Some of them just grabbed mats and settled down for a nap, but most dropped their gear and headed toward the mess hall.

They’d have to start paying for meals as soon as their term was over, and that would be just as soon as Chang Wu got around to paying them for this last leg. For most of them, it was the journey from Karida to Eudoxia.

“Damn, finally some crowns!” said Robert. “As soon as I get paid I’m outta here.”

“I know some places with pretty good ale,” suggested Kostubh. “Been through here a few times.”

“Nah, any old ale’s fine with me. Time to go find a woman.”

Kostubh hesitated.

He’d been drinking, little by little, for a few years now, but he was still a virgin. Karadi hadn’t actually forbidden him, but his parents seemed to know everything that happened in Shiroora Shan, and when they were on the road somewhere the guards always kept pretty close.

He was interested, sure, but... a little scared, too.

“Mind if I keep you company? Wouldn’t mind a little companionship myself,” he said, trying to sound smooth.

“Hey, sure! Might blow your coin, though.”

“That’s OK. It’s too heavy to lug around all the time anyway,” he chuckled.

They loaded up on deino stew and rough black bread at the cafeteria, washed down with lukewarm tea, then lounged about until Chang got around to them.

“How much you getting paid?” asked Robert. “Just the trip from Shiroora Shan.”

Kostubh didn’t have a clue... he had his own money from gambling, and it had never occurred to him that he might be getting paid like everyone else. Or was he?

He decided to play it safe.

“Nothing, yet. I don’t get paid until we reach Despina.”

“You sure you’ve got enough for the girls?”

“I saved up special,” he smiled. “No worries.”

“Hey, Robert! Get your ass over here!”

It was Ran, shouting from the other end of the hall.

“Master Chang wants to see you!”

Robert flashed a grin at Kostubh and stood. It was a short walk to where Chang Wu was sitting, and while Kostbh couldn’t hear what they were saying, he could see Chang handing Robert a bag of money.

Robert bowed and came walking back, tucking the bag into his wallet with a smile on his face.

“Got a bonus, too... Gonna have some fun tonight!”

Ran shouted for the next person, and eventually Kostubh heard his own name.

Chang Wu cocked his head and looked up at Kostubh standing in front of him.

“Master Bulbuk says I shouldn’t pay you. You OK with that?”

“Yeah, whatever... It’d look bad to pay me so soon anyway.”

“You’re right about that,” nodded the seated man. “Anyway, you’re with us to Despina. You work like everyone else, you’ll get paid like everyone else.”

“Yup.”

“You know why Master Bulbuk agreed to let you join us?”

“My father told me he once saved Master Bulbuk’s life.”

“That’s right. A long time ago, in Karida. This is partial payment on that debt.

“That doesn’t mean you can lounge about, though... He said to treat you just like one of the regulars, and that’s what I’m going to do. Screw up and I’ll leave you by the side of the road, debt or no debt.”

“Sure, no problem, Chang. I’ll be hap—"

“That’s Master Chang to you, Kostubh. And you won’t be anything, kid, except a good worker, or you’re out on your ass, that clear?”

Kostubh gritted his teeth and managed to stay silent.

He nodded, turned, and walked back to where Robert was waiting.

“Looks like you and Chang have a little problem there.”

“Ah, fuck Chang. Let’s get outta here,” he said, and spat on the ground. “Hang on for a sec, I gotta go bum some cash. Be right back!”

He left Robert waiting and walked into the office to find his brother, who was checking a cargo list with one of Than Bulbuk’s cargo handlers.

“Hey, Gitanshu. You gotta sec?”

Gitanshu slammed his hand on the tabletop and spun around, stepping toward Kostubh.

“That’s Master Gitanshu to you. And what are you doing wandering around in here anyway?”

“I... Wow, what’s the big deal?”

“Leave. Now,” said his brother, pointing at the door in fury. He turned to the other man. “I’ll be right back. Let me get rid of this insolent child.”

Kostubh started to protest, but Gitanshu grabbed him by the arm and manhandled him to the doorway. “Silence! Not one more word.”

He pushed Kostubh out of the door, and stepped out next to him.

“What the hell is wrong with you!? I told you you’d be treated like everyone else. People find out I’m your brother and we’ll both be in trouble. Now get out of here.”

“Gimme some cash and I won’t bug you again,” said Kostubh. “I don’t get paid until Despina.”

“You’d better grow up fast, Kostubh. House Chabra doesn’t mean shit out here,” warned Gitanshu, but handed him a handful of coins. “Next time, it’s Master Gitanshu, and don’t forget it!”

He gave Kostubh another shove toward the compound gate and turned back to his work.

Robert was still waiting.

It was already starting to get dark. They were both a little tired from moving all the cargo around—once off the boat, and then again off the wagons—and just having eaten, but the thrill of getting out for a night of fun was more important than a nap.

“Where to?”

“The sailors were gossiping about a place called Lili’s,” said Robert. “There’s some Zarite girl there that drives you wild. C’mon, let’s go!”

Awestruck by Robert’s familiarity with women, Kostubh nodded and followed.

Seen from the street, Lili’s was the usual white-washed, mud brick building, with a dimly lit tavern on the first floor and smaller rooms upstairs. It was about half full, and Kostubh noticed half a dozen women along the stairs wearing revealing clothing. In one case, very close to nothing at all.

A very large red-haired man stood at the bottom of the stairway, twin daggers at his belt.

“One crown,” he said, holding his hand out to Kostubh, who slapped the coin down without hesitation and pushed Robert up the stairway.

He stopped and looked back at Kostubh to see if he was coming up, too, but Kostubh just laughed.

A woman with long blond hair, maybe from Lomar, stood to greet Robert, and took his hand in hers. She didn’t have to guide him: he dropped his hand to her ass and practically pushed her up the stairs.

He glanced back one last time.

“You coming, Kostubh?”

“In a bit,” he called. “Ale first.”

Kostubh watched his friend vanish into the second floor, and stood for a moment, hand on his wallet, lost in thought. He started to pull a second crown out, then changed his mind and turned toward the counter.

He took a step forward, stopped for a moment and glanced upstairs, then stepped up to the counter.

“Got any Zeenar pale ale?”

The man behind the counter laughed.

“Well, well, well, the little prince, huh? We got ale, and we got wine, and we got some Shang jitsu about, but we ain’t got any Zeenar pale ale.”

“Uh, ale, then.”

A mug-full of warm ale slapped down on the counter.

“That’ll be a copper.”

Kostubh slid a laurel across the countertop, to be snapped up by the other.

He took a sip and frowned.

It wasn’t very good ale

Robert had already vanished upstairs, and he didn’t recognize anyone in the tavern.

“Buy me a drink, too, would ya?”

He turned at the woman’s voice to see a dark-eyed woman with reddish-brown hair, only a few years older than himself. She was dressed in a simple but very low-cut tunic, with a triple strand of blue beads around her neck.

“Uh, yeah, sure.”

He turned back to order another ale, but the barkeep was already there, slapping a second mug of something in front of her.

The barkeep held out his hand and Kostubh dropped another copper into it.

She took a sip and placed it back on the countertop.

“Where you from? Somewhere east, I bet.”

“Shiroora Shan,” he answered. “Came over on a caravan.”

“Oh, so you just got in!” she said, smiling and placing one hand lightly on his thigh. “First night, huh?”

“Yeah.”

“You all alone?”

“For now. My buddy’s upstairs.”

“Oh, you poor man,” she sympathized. “This is your first visit, isn’t it?”

He nodded, blushing.

“A handsome man like you! I’ll take good care of you, don’t worry—a night you’ll never forget. Why don’t we go upstairs and get more comfortable?”

She wrapped herself around him, practically dragged him toward the staircase, her breasts rubbing against his chest.

“It’ll cost you a crown,” she said, “but I’m worth it, you’ll see.”

He eagerly pulled a handful of coins from his wallet, picked one crown out and pressed it into her hand.

“There’s more ale upstairs,” she whispered, eyeing the heft of his wallet. “On the house.”

Her hand slipped a little on his thigh, touching him briefly.

“Oh, my, you just can’t wait, can you?”

The room was smaller than the bath he’d used at House Chabra, barely big enough for a sleeping mat and a low shelf with a bottle, some cups, and a wad of thagweed.

She broke off some of the thagweed, crumbling it in her fingers into the cup, then poured the liquid over it. Whatever it was, it was mostly alcohol, he thought. He could smell it from where he was sitting.

“Just drink it down like a good boy,” she smiled, “and let me get ready.”

He’d tried thagweed a couple times and absolutely hated the taste, but he loved the way his senses expanded... and the sight of her naked body excited him so much he didn’t even notice the taste.

Her hand moved up under his tunic and he froze as it grasped his cock and began to stroke it, then hesitantly reached out to touch her breast.

Already he could feel the thagweed taking effect, accelerated by the alcohol, his senses expanding. He could smell her body, her heat, hear her pulse even over the pounding of his own heart, feel the smoothness of her skin and the tiny bumps around her nipples.

He groaned at the sensory overload and leaned forward to take a nipple into his mouth. He tongued it, back and forth, feeling it slowly grow harder, and felt the soft, comforting darkness closing in. He was so sleepy...

* * *

“Get up, you drunken lout!”

The shout was accompanied by a painful whack to his ass with a broom.

He tried to open his eyes, blinded by the sunlight.

A second whack woke him up completely, and he got a better look at where he was—lying in a filthy alley surrounded by garbage, face flush against the slimy cobblestones.

A pair of large sandals was in front of his nose, connected to a pair of stocky, quite muscular legs.

“Up, boy!”

He scrambled to his feet before a third whack could find its target.

He had a splitting headache, and his mouth tasted like camel shit.

He swayed for a second, caught himself, looked at the woman holding the broom.

In her fifties, he guessed. Dumpy, tired, dressed in well-worn clothes, broom and bucket in hand.

“Where—?”

“So drunk you can’t remember where you are, young man? Not my problem,” she scolded, sweeping garbage to the side and dragging the broom over his bare feet in the process. “Off with you now, or I’ll throw you out with the rest of the trash.”

He tried to remember what had happened. Lili’s place, right. With Robert. He looked around, and spotted a leg sticking out from behind a nearby pile of stones.

He took a step and noticed he only had one sandal.... no sign of the other one.

He gave up and stumbled over to see who was lying there.

It was Robert, snoring like a baby.

He slapped him lightly a few times until finally one eye opened and he sat up, groaning.

“What the fu... where are we?”

“I think we’re in the back alley behind Lili’s,” said Kostubh.

Robert hurriedly checked his waist, then twisted to his knees to look around.

“Shit. My wallet’s gone. That’s all I had, until we get to Despina.”

Kostubh grabbed for his own wallet—it was gone.

“Fuck! Fuck! Fuck!” screamed Kostubh, kicking the innocent pile of stones. “I’ll fucking kill those bitches!”

“No swords, either,” pointed out Robert. “Let’s get back to Bulbuk’s place; I want to wash up.”

Kostubh picked up a handy length of wood and tested it against his hand.

“Don’t need a sword,” he snarled. “Which one of these is Lili’s?”

“Leave it, Kostubh,” warned Robert, one hand on the piece of wood and the other on Kostubh’s shoulder. “You don’t have a chance.”

Kostubh shook him off and stomped down the alley into one of the larger streets. He looked around to catch his bearings, then stalked toward the entrance to Lili’s, with Robert close behind.

The door was shut, of course, this early in the morning, but he hammered on it with his fist anyway.

“Open up, you bastards! I want my fucking money back!”

The door suddenly open, outwards, knocking him off balance for a minute, and as he staggered backwards a large man—the same redhead who’d been guarding the staircase last night—stepped out, his sword pointed at Kostubh’s throat.

“I dunno who you are, don’ care. Go away or I’ll spit you like a pig.”

“You rolled me—us—and stole our money, you thief!”

“I didn’ steal nothin’. Now git the fuck away from here, boy!”

He prodded Kostubh with his sword for emphasis.

Unarmed, Kotsubh let Robert pull him away.

“I told you to forget it, Kostubh! Leave it be!”

“Sons of bitches! I’ll be back to settle up with you later!”

He kicked out at a passing dog in anger, but missed and got a flash of bared teeth for his trouble.

In spite of looking and smelling like they crawled from some sewer, the guard at Than Bulbuk’s compound grudgingly let them back in.

* * *

Everyone else laughed at the whole thing; some of them had their own experiences to share. Robert and Kostubh—especially Kostubh—hated being needled about it.

Robert didn’t seem very upset at losing his money and his sword, but Kostubh seethed.

It was pretty much forgotten the next day, of course, as they were all busy getting the cargo packed and ready for the next leg of the trip. Most of the crystal from Shiroora Shan and the Gondaran paper and silk was destined for Rinar, where it would be split into shipments to the other three major sea-trade hubs of Dylath-Leen, Celephaïs, and Pungar-Vees, with some distributed to the cities that Rinar served directly. Than Bulbuk wouldn’t be involved in any of those transactions, selling the entirety of his wares to other traders—and a few merchants—in Rinar.

Chóng Lán of Penglai had been pressing him for years for an exclusive arrangement while simultaneously trying to set up his own parallel network, but so far Than Bulbuk had managed to preserve both his independence and his profits.

Once he’d sold his goods in Rinar he’d purchase goods heading in the other direction, eastward back toward Eudoxia, Shiroora Shan, and the cities of the steppes beyond the Night Ocean. He hoped to pick up some of the fragrant resins and perfumes of Oriab, fine porcelain from Baharna, hopefully some of the iridescent fabrics of Hatheg, and maybe even some spider-silk from Moung. He’d carry more common goods as well: Ulthar wool, copper ingot and worked brass from Aphorat, Kadatheron cork, apples from Sinara and Jaren.

Finally Chang Wu, the loadmaster, said everything was ready, and they’d be leaving at first light.

“I’ll need you awake and alert tomorrow, so if there’s anything you need to do in Eudoxia get it done and get rested up. Anyone sleeping on the road will be walking back.”

There was a rumble of conversation from the crowd, and they broke up into smaller groups, some people breaking off alone.

“Let’s go get our money back,” said Kostubh, grabbing Robert by the shoulder. “Bastards!”

“That guy at the door looks a lot stronger than me.”

“Yeah, well, fuck him. There’s two of us, right?”

Robert shook his head.

“Sorry, Kostubh, I’m out. It’s not worth getting killed over.”

“Well then fuck you too!” snarled Kostubh, shoving Robert away and stomping off toward the gate. “I’m going, with or without you.”

Robert hesitated as Kostubh stalked through the gate and started down the road, then cursed and ran after him.

“I still think it’s a stupid idea and it’ll get us killed, you asshole. Let it go!”

Kostubh was silent, fingering the newly borrowed sword hanging at his side.

“At least wait until it’s dark!”

Kostubh’s footsteps slowed.

“That’s not a bad idea, actually... Let’s grab some eats first; it’ll be dark soon enough.”

They headed toward the market, packed with people of all sorts buying and selling almost everything under the sun, and all of it at the top of their lungs.

Kostubh picked out a small stand selling po, the steamed buns of the Ibizim. They were stuffed with a variety of spicy meat and vegetables.

“That’ll be a copper apiece, lads,” said the cook as he put pulled a leaf from the pile and dropped two steaming po onto it.

“Here,” said Kostubh, handing over some coins. “Make it four; we’re hungry.”

The cook glanced at the coins.

“This is only three laurels...”

“Yeah, three coppers is enough. Or we can go somewhere else,” sniffed Kostubh, holding out a hand for the leaf. “Put the other two on another leaf for my friend here.”

The cook hesitated for a moment, then silently pulled out another leaf and dropped two more buns on it, handing it to Robert.

They walked through the market as they ate, eyeing the enormous variety of goods and food on display.

“It’s only another copper, Kostubh...” said Robert quietly. “Why not just pay the man?”

“Ah, fuck ’im,” said Kostubh around a mouthful of hot bun. “He’s just a peasant.”

He turned to look at Robert more closely.

“You’re not serious, are you? You can’t go around paying these people what they ask for! You can always drop the price. Or say you found a dead rat in it!”

He laughed at his own jest, missing the twitch of disgust that flashed across Robert’s face.

“No, of course not,...” he agreed. “Just peasants, after all.”

Kostubh nodded his head several times in agreement as he wiped his hands on his tunic.

“Go over there are shout you saw a snake,” he said, pointing to a nearby stall.

“A snake...? What...?”

“Just do it, Robert,” said Kostubh, giving him a shove. “Sound scared!”

The other man shrugged and walked over to where Kostubh had pointed, looking at the fresh turnips displayed by a farmer in passing.

“Pulled ’em this mornin’,” he said, waving a leafy bundle with clods of dirt falling off.

Robert shook his head, holding up one hand to stop the man’s spiel, and kept walking as directed toward a small wagon selling some sort of reddish pottery.

He bent forward a little as if to get a better look, and then leapt backwards to fall on his ass, screaming “A viper! There’s a viper! Right there!”

Everyone who could hear him jumped one way or another, some trying to run away and some hoping to kill the snake. The market was so noisy that his screams only carried a few meters, but it was enough to cause a sudden squall of excitement.

Robert quickly backpedaled from the pottery seller’s wagon, catching up to Kostubh as he was walking away from the scene.

“Hey, what was all that about?”

Kostubh pulled him around a stack of carpets, out of sight of the rapidly cooling viper scare, and handed him an apple.

“There you are,” he said proudly, and took a second one from his wallet. “Compliments of that fruit cart just now.”

“Wait, you had me scream ‘snake’ just to rip off a couple apples?”

“Yeah,” said Kostubh, taking another bite. “Good ones, too!”

“You’re gonna get the Guard after us,” moaned Robert.

“Nah, fuck ’em all. They should thank me for eating their crap.”

Robert stared at the beautiful, red apple in his hand for a moment, then took a bite.

“Good, huh?”

“Yeah, good,” he agreed, and took another.

They wandered through the marketplace for another hour or so, just wasting time until it was dark. Once, Robert said he wished he had more money, looking wistfully at an engraved steel dagger, Kostubh found a way to steal it out from under the eyes of the shopkeeper, and pulled it out of his tunic later to a flabbergasted Robert.

“Here, you said you really liked this.”

“You got it for... wait a minute. You stole it for me?”

“Nah,” said Kostubh with a wave of his hand. “The shopkeeper gave it to me because I’m a Chabra. Keep it!”

Robert hefted it a few times, and practiced a stab.

“Have to get a decent sheath for it, too,” he said, grinning. “Thanks!”

“Sure,” said Kostubh, looking up at the sky. “It’s pretty dark... let’s head over there and see, huh?”

They both remembered where Lili’s was, and a short time later stood in the shadows across the road, watching the entrance.

The same red-haired guard stood there, making sure that only paying customers got in. He was big, armed, and obviously quite capable of using that sword if he had to.

“So what’re you gonna do? Just walk over there and stab him?”

“Doesn’t look like much to me,” sniffed Kostubh. “I don’t want to get my tunic dirty, though.

“Nah, this is a whole lot easier.”

He reached up and removed two of the oil lanterns hanging from a nearby street stall, and shook them once or twice, listening to see how much oil was inside.

“Oh, yeah, this’ll do nicely,” he smiled, and looked across the road, judging the distance.

“Kostubh! No!”

He stretched his arm out and whipped it forward, launching the lantern across the road and through Lili’s window. There was the sound of breaking glass and then a muffled whump as the spilled oil ignited. The second lantern followed almost immediately.

“Fire! Fire!”

“Quick, get water!”

“It’s spreading to the curtain!”

The guard at the front door half-drew his sword and glared in their direction, but at the screams he stopped and slammed the sword back into its sheath. With a curse he grabbed a nearby bucket and raced toward the nearest well, some hundred meters down the road.

“Kostubh of Shiroora-Shan, you’re a dead man!” he shouted as he ran.

“What the hell, Kostubh? You out of your mind?”

“Fuckers stole my money, that’s what they get,” snarled Kostubh, turning away from the spreading conflagration behind him and walking back the way they’d come. “I hope the whole place burns down, and that bitch with it!”

Robert stared at him, aghast, then glanced back at the black silhouettes struggling to contain the flames. Kostubh kept walking, though, and Robert trotted after him, away from the blaze and into the darkness.

“Kostubh, they won’t let us back into the compound this late... and the city guard’ll be after us soon enough. What’re we gonna do?”

Kostubh halted and turned to face him, the whites of his eyes pale in the night.

“Of course they’ll let us in! I’m a Chabra!”

“You’re a fucking idiot! You just set fire to that place, maybe killed some people, and the whole guard’ll be looking for you, Kostubh of Shiroora-Shan. And me. And the first place they’ll look’ll be Bulbuk’s compound.

“You can’t go doing all this shit and expect to get away with it because you’re a fuckin’ Chabra! That doesn’t mean a damn thing here! They catch us, they’ll chop our damn heads off!”

“They’d never kill me, son of Karadi Chabra of Shiroora-Shan.”

Robert grabbed the other man by the shoulders and shook him, hard.

“Listen to me, you idiot! Chabra doesn’t mean shit here! They.Will.Kill.Us.”

Kostubh stilled, shuffled his feet, spat once, looked up at the few stars visible between the overhanging roofs.

“You’re serious...”

“Yeah I’m serious!” said Robert. “We can’t go back to Bulbuk—he’d turn us over to the guard himself. And if we stay here they’ll catch us sooner or later. Probably sooner, because they know the city and we don’t have anywhere to go. We’re fucking dead, Kostubh!”

There was silence for a moment, then the faint sound of a crying baby from somewhere nearby.

“C’mon, this way,” said Kostubh suddenly, tapping Robert on the shoulder and heading for the compound.

“We can’t...”

“Yeah, we can. Shut up.”

When they reached the compound, the guards refused to let them in, just as Robert had warned.

“Call Master Gitanshu,” asked Kostubh. “It’s urgent.”

“I’m not going to go bother Master Gitanshu for a couple drunks!”

“Maybe this’ll make it easier,” said Kostubh, handing over what was left of the money he got from his brother.

The guard weighed it, sniffed, hitched up his sword belt, and turned to hand some of the coins to the other guard.

“Keep an eye on these two, will ‘ya? And if they’re fuckin’ with us we can take it outta their hides.”

The other guard nodded, hand on the pommel of his sword.

Gitanshu showed up only a few minutes later.

“What is it now, Kostubh? I have better things to do than babysit you!”

“Sorry, but I’ve—we’ve—got a little problem,” explained Kostubh, leading his brother away from the ears of the waiting guard. “There’s been a misunderstanding and the city guard’ll probably be here looking for us later.”

“If you’ve done anything to hurt Master Than Bulbuk I’ll hand you over myself!”

“Oh, no, nothing like that. Strictly a misunderstanding, but one that would take time to clear up. Rather than getting into a complicated argument with the guard, possibly delaying departure tomorrow, it might be easier to just hide us until we’re out of Eudoxia.”

“And then what? They’ll figure it out, Kostubh, and come after you.”

“And then we’ll leave the caravan in Thace, or Despina, and it’ll be as if we were never there.”

“Everywhere we go I have to clean up after you!” raged Gitanshu. “This is the last time! Come with me and I’ll find a way to get you out of the city, but I want you out of this caravan in Thace! Got it?”

“Of course, brother, no problem at all,” smiled Kostubh, and winked at Robert. “We’ll leave long before the guard might cause any problem.”

Gitanshu spit and cursed under his breath.

“You two leave now. Make sure the guards see you leaving. Go around to the mill entrance, on the east side, and I’ll let you in there. And don’t screw it up!”

“Thanks, Gitanshu. I knew I could count on you.”

“Fuck you, Kostubh. And you—what’s your name?”

“Robert, Master Gitanshu. Thank you for helping us out.”

“I don’t know how he roped you into this, but you’re his now. And I want you gone with him.”

Gitanshu stomped back to the guard cursing, and then turned back to the two waiting men.

“No, I won’t let you in, you drunkards! Now get out of here before I call the city guard myself!”

He stopped next the guard and clapped him on the shoulder.

“They won’t be back, because they don’t work for Master Than Bulbuk anymore. If they try to get in you should spit them like any other thief.”

The guard grinned and nodded.

“Yessir, sorry to have bothered you, sir. They won’t be gettin’ in.”

“Good man,” said Gitanshu, nodding sharply and striding back into the compound.

The guard glared at Kostubh and Robert, who slunk back into the darkness.

* * *

Early that afternoon Kostubh woke up suddenly when the camel stopped. He’d been banging around in the wicker basket for hours, strapped to the side of one of the cargo camels, and had fallen into a sort of half-sleep, half-delirium state due to the heat.

“Kostubh!”

He recognized the whisper, of course. It was Gitanshu.

“Kostubh? You OK in there?”

He groaned and tried to force words out of his parched mouth.

“Awa..... wa... wa–ter...”

The basket hasp opened and his brother’s silhouette looked down at him through the blinding sunlight. Through the tears he saw a huge black hand descending, and instinctively shied away, holding up one hand in defense.

The waterskin hit his hand and he sighed at the incredible delight of the cool water inside.

He grabbed it from Gitanshu’s hand and drank ferociously, spilling a good bit in the process.

“Keep it,” said his brother. “Give me the old one and I’ll fill it up again for you.”

“Aahhhh...”

Kostubh finally pulled the waterskin from his mouth, sated.

He breathed for a moment, enjoying the freedom of the open basket, and licked his lips.

“I thought you were trying to kill me, Gitanshu! Locked up in there, banging about like a damned potato. A well-baked damned potato!”

Gitanshu shrugged.

“No other way to get you out of Eudoxia. You know that. They stopped and questioned us, you know, looking for you. You and Robert. Master Than Bulbuk is furious, but said he owed father that much.”

“How about some food, too?”

“I’ll see if I can sneak something to you. If you need to take a piss, better get it done now—I’ve blocked off the view from the caravan, so you can get out of there for a few minutes.”

Kostubh managed to drag himself out of the basket, collapsing onto the ground in a heap as his legs gave out from under him. Robert joined him momentarily.

Robert just sat on the sand massaging his legs with one hand and drinking with the other.

“Kostubh, we’ve had it with you. I begged Master Than Bulbuk to look the other way this time, but you’ve repaid his trust terribly, blackened your name forever. And his name, and my name, and even our father’s name.”

Kostubh shrugged and jumped up and down experimentally.

“Like I said just a misunderstanding. We’re out of the city and nobody saw us, right? So no harm done, I’d say.”

“It wasn’t a misunderstanding, you maniac! You burned down three buildings and they say one person died in the blaze! That’s not a misunderstanding, and if you ever go back to Eudoxia they’ll spike your head on the city wall.”

“So I won’t go back to Eudoxia. Plenty of other places to go.”

“It’ll take about another five or six days to reach Thace,” said Gitanshu, “but Master Than Bulbuk wants you gone tonight. I’ll give you two horses when we make camp.

“He’s already sent a dragolet to father with a complete explanation and refuses to reconsider.”

“Two horses, huh?” asked Kostubh, looking interested for the first time. “And supplies?”

“Yes, of course with supplies. If I wanted you dead all I had to do was hand you over to the guard,” said Gitanshu in exasperation. “We’re still in the foothills of the Hills of Noor, not the desert, so you shouldn’t have much difficulty.”

“I’ll be gone, then, assuming I survive this torture until nightfall,” said Kostubh, nodding.

“What about you, Master Robert?”

Robert looked up suddenly, not expecting to be addressed.

“Uh... I’ll go along with him, Master Gitanshu, thank you.”

“So both you, then. Two horses, supplies, arms... I’ll have it ready to go.”

“Thanks, Gitanshu,” smiled Kostubh. “I knew I could count on you.”

“I’m not helping you because I want to, Kostubh. You’re dangerous and I want you gone before you ruin Master Than Bulbuk and me with him!”

“Yeah, whatever. I love you too, Gitanshu.

“Just give us the word and we’ll be gone.”

As Gitanshu stomped off fuming, Kostubh looked around at the caravan.

They were stopped for lunch and a rest, heading north at the foot of the Hills of Noor.. The mountains shielded them from the morning sun, and runoff usually meant there was sparse groundcover for much of the way. A few days from now the trail would turn west, away from the Hills of Noor—a mountain range, in spite of the name—and toward Thace, into the desert proper.

Except for a few people tending to their animals—the caravan had both horses and camels, but of course no deinos on the desert road—and a group of three cursing men trying to repair a bent cartwheel, everyone was eating or lounging. Sunshades and a few shimmers were up, keeping the heat down to a reasonable level.

They stayed hidden, knowing that any of the caravan crew would betray them to the city guard without a moment’s hesitation. They were half a day’s ride from Eudoxia, but there was no way of telling where the guard might be.

They’d just have to suffer in silence until nightfall.

Gitanshu was back in a few minutes with a pot of warm, spicy beans and a stack of bread to eat it with.

“Can’t even bring us an ale to go with it?”

“Drink your water and be happy I got you this much,” said Gitanshu sourly. “And make sure you’re back in your baskets as soon as you hear everyone start to gear up for the afternoon ride.”

“Yeah, yeah, whatever,” said Kostubh through a mouthful of bread. “Don’t worry, we won’t embarrass you.”

“You already did that quite adequately,” said Gitanshu.

They climbed back into their reed prisons about half an hour later as the caravan began preparing to set out once again, and a few minutes Gitanshu dropped by to make sure the baskets were securely fastened, and their hidden occupants invisible.

“Enjoy your ride!” he whispered gayly, rapping on Kostubh’s basket.

“Fuck you.”

* * *

That night they finally took their leave of Than Bulbuk’s caravan, thanks to Gitanshu. He’d wheedled the trader into providing two horses (not the finest steeds, true, but certainly an improvement over walking) and a modest amount of supplies.

Than Bulbuk refused to even meet them, so that he could continue to truthfully say that he had not seen them in his caravan.

Gitanshu was quietly furious and while he didn’t discuss what the whole situation had cost him in terms of Than Bulbuk’s trust or possibly even gold, there was little doubt that Kostubh had used up his welcome.

They slowly rode away from the caravan’s night camp, east deeper into the mountains, and by dawn should be well on their way.

Kostubh suddenly slowed his pace and guided the horse over to a stand of trees. He dismounted, and tethered the horse to a tree hidden in the darkness.

“Watch the horses,” he ordered to Robert. “One last thing to do before we leave.”

“You’re not going back are you?”

Kostubh grinned.

“Don’t you worry about it. I’ll be back before you know I’m gone,” and slipped off into the night.

True to his word he was back in a little over an hour.

He untied the rope and climbed back up into the saddle grinning widely.

“What are you so happy about? What did you do?”

Kostubh held a large handful of coins out for Robert to see, and dropped them into his surprised hand.

“Where’d you get the money? You didn’t rob Master Than Bulbuk did you!?”

“Of course not. I just paid a little visit to our own friend Ran, and relieved him of some excess baggage. He was sleeping like a baby; didn’t notice a thing.

“In fact, since his wallet is now full of gravel instead of coins, he may not notice anything until they reach Thace and he tries to pay for something!”

Robert laughed, delighted. That took care of his own debt to Ran, too, he realized.

“As far as anyone knows we left the caravan in Eudoxia, so he’ll no doubt make life difficult for everyone else, trying to figure out who stole his money. Poor fools.”

“He deserves it. Hell, he deserves a lot more than that, the way he treated me,” agreed Kostubh. “And you, of course.”

Without waiting for Robert’s response he kicked his horse lightly and began to trot again in the wan light of the half-moon.

Robert hurried to catch up, settling his horse into position just behind him.

“Where are we going?”

“Well, we can’t go back to Eudoxia, and we can’t go to Thrace, at least not until Bulbuk leaves,” replied Kostubh. “I’m heading for the Oasis of Noor. Ever been there?”

“Noor? Nope. What’s there?”

“Once we get to the Oasis, we can take the route through the mountains to Nurl, hook up with a caravan heading north on either side of the Hills, or even turn west and head for Mnar.”

“Mnar? That’s where Sarnath is, right?”

“Yeah, the lake and Ib and all that. I don’t know how much of that is true, but might be a good idea to stay well away.”

“Hell yeah!”

They continued north, paralleling the Hills. In spite of the name, the Hills of Noor were only hills well to the south, where they sank into the Night Ocean. They grew in height northward into a major range. They were still well to the south—the Oasis roughly marked the halfway point in the range—but the mountains were already high enough that the horses would have been largely useless.

It was much easier to ride at the base of the mountains, with the Liranian Desert stretching off to the west on one side and the mountains to the east. There was plenty of grass for the horses to eat, watered by mountain streams, and since they weren’t in any particular hurry they could relax and take the easy route.

The easy route also meant rabbits and deer, and they finally reached the outskirts of the Oasis days later well fed and rested.

The Oasis of Noor was actually a small lake, fed by several streams running down out of the mountains. It had no known outlet, but standing as it did on the edge of the Liranian Desert there was no doubt that the dry sands drank every drop.

There was a route threading through the Hills of Noor, east, to Nurl. Horses and camels could use it safely, but it had a number of narrow sections that few wagons could pass. There was also a trade road connecting it to Thace to the south, and northward. The road north ran though the western bulge of the Hills and then into the desert to Tsol and beyond.

From Tsol there were numerous possibilities: they could travel farther west, through the Mohagger Mountains encircling the Lake of Sarnath, or continue northwest towards Tsun.

There were always caravans on the ancient trade roads through the desert, guided through the waste by the wind-worn statues standing silently every few kilometers.

The scrub dotting the flanks of the mountains gradually gave way to greener leaves and taller trees as they approached the Oasis. The greenery was a pleasant sight for eyes tired of endless sand and rock, and the horses appreciated the change to fresh green grass.

Kostubh was even whistling once in a while, obviously far less affected by their situation that Robert, who seemed quite worried that someone might be pursuing them. He looked over this shoulder often, and half-drew his sword at the slightest noise.

There was never a sign of any pursuit, though, even though they doubled back once just to see if there were any other tracks.

As the Oasis of Noor grew closer, though, even Kostubh began to think about what might be waiting there.

“We came here along the fastest road from Eudoxia,” he said, “and nobody passed us on the way. I don’t see why anyone should be waiting for us.”

“They could have used dragolets.”

“Sure, they could, but why would they? Even assuming they actually have a dragolet pair for the Oasis,” he countered. “Besides, if they look for us at all, they’ve already checked the caravan and didn’t find us. They have no reason to think we’re heading to Noor, or the desert.

“I figure the Boorsh Fen is where they’re looking. If they’re even looking at all.”

“Maybe,” Robert agreed grudgingly. “But...”

“Relax, everything’s fine. Just leave it up to me.”

Kostubh reined his horses to a halt and slid off.

“I’m gonna slip up ahead and see what the Oasis looks like. Don’t know much about it.”

“Me neither,” agreed Robert. “Let me go with you.”

“Nah, keep an eye on the horses, will ya? I won’t be back for a few hours.”

Kostubh handed his reins to Robert and adjusted his sword belt, then melted into the underbrush.

The Oasis of Noor was just ahead of them, at the base of the mountain’s slope. The bushes and trees were getting higher, but it was possible to see quite a bit from their vantage point.

What they could see consisted of open water, palm trees surrounded by lower vegetation, and a handful of buildings built variously of stone or wood. It was early morning, the sun still low over the Hills of Noor behind him. Shadows were long and dark.

Kostubh had been taught well by his father, master hunter Karadi, and moved silently through the brush. He moved closer to the main road, running into the Oasis from Thace to the south. Most trade from Thace traveled west, heading for Despina, but there was also considerable traffic from Thace to the Oasis, then west along the desert’s edge, trending gradually northwest, and beyond.

Kostubh was pretty sure that nobody from Eudoxia could have gotten here before them, but it wouldn’t hurt to watch the road for a bit and try to get a better idea of how busy—and dangerous—things were.

He picked a nice thick tangle of brush to hide in, right next to the main road where a tiny footpath ran off deeper into the mountains. In the shadows under the brush, he was effectively invisible.

About half an hour later a horse-drawn wagon piled with bales of hay plodded by. Kostubh figured it must be from some pasture nearby, brought here to feed the animals. And probably sell to people passing through. The fresh grass around the oasis was great while they were here, but once they left and entered the desert, grain or dried hay lasted a lot longer than fresh leaves.

A wagonload of hay was not much of a threat, though.

He yawned and kept waiting.

A few other innocuous people passed by in one direction or the other: traders, farmers, one Godsworn with acolytes, a few traveling alone for no apparent reason. All in all, though, perfectly normal.

The sun was high, around noon.

Just as he was thinking that he might as well go get Robert and ride into the Oasis, he heard clashing swords and shouts.

He twisted to the side so he could see better.

He could just see a small covered wagon, gaily carved and painted in brilliant colors. Looked like an itinerant Rom family, he thought to himself.

The main man of the family was dying messily in the dirt, screaming in agony as his guts spilled out. Two of his two attackers were now ganging up on a boy standing between them and the wagon. He was trying, but he was too inexperienced, and too weak... even as Kostubh watched, one of the robbers knocked the sword out of the boy’s hand with his own sword. The other robber took advantage of the opening to thrust deep into the boy’s side. The boy screamed and staggered sideways until a sword in the back toppled him.

Behind them another robber already had a youngish girl on the ground, enthusiastically pumping away as she screamed, and tried to push him away. He laughed at her screams and weak fists.

Two more were already climbing up the wagon, battering its wooden door open with their weapons. They finally chopped it open and eagerly tore it out of the way, crowding in, weapons drawn.

The wagon shook, more screams, and suddenly a woman leapt out of the wagon through the front, onto the driver’s bench, then down to the road, carrying something in her arms.

The two robbers scrambled out of the wagon after her, joined by the two who had just killed the boy.

She was running right toward him!

Kostubh couldn’t squirm backwards without raising a commotion, and he couldn’t win against four or five well-armed men, especially lying down. He moved his head to hide behind the leaves more effectively.

She was carrying a baby.

The woman saw the path off into the mountains, and ran toward it, her pursuer growing closer.

Bad luck again as she stumbled and fell, barely catching herself on her free hand as she protected her baby with the other.

Their eyes met.

She froze for the merest fraction of a second, entreating him to save her child. She knew she was doomed to rape, possibly slavery or more probably death.

But he could save her baby; her pursuers would leave it to die, or kill it outright.

After what felt like a decade time started ticking again, and she thrust the baby into the underbrush right in front of his nose.

She whispered a single word—Peanna—and yanked a branch down to hide them.

She was up and running again instantly, as if she had merely stumbled and caught herself, but Kostubh could still see her brown eyes beseeching him as she ran.

A moment later he heard more shouting, and a woman screaming, and laughter.

They’d caught her.

While they were busy with their prey, he had a chance to get away to safety.

But what to do with the baby?

He looked down at the child for the first time, and it—she—looked up at him, silent and still, huge eyes transfixing him.

“... Hansika...?”

Peanna, her mother had called her. She looked exactly like his little sister. Hansika was only fourteen, and the baby was older than he’d thought. Two, maybe? He didn’t really know much about babies or young children, as he was one of the youngest of the Chabra children and had never really had to babysit anyone.

But in spite of the age difference, the child looked just like Hansika. The same eyes, the same nose...

He couldn’t just leave her here to die.

But he didn’t know how to take care of a kid!

Still holding the silent child in his arms, he wriggled backwards away from the road until he could rise to a crouch, then left the area as quickly as he could.

Robert was right where he’d left him.

“We’re leaving,” he said in a low voice. “Right now, and stay quiet, on your life.”

Robert nodded and unhobbled his horse. He glanced at Kostubh and raised an eyebrow.

“Robbers. Now, quietly.”

They led their horses back up the slope, deeper into the mountains, away from the Oasis.

Kostubh carried Peanna in his arms all the way

* * *

The small fire lit the walls of the cave in red and orange, black shadows dancing as the flames leaped.

Pursuers, if there were any, might be able to spot the fire if they were close enough, but they were well off the road and the entrance to the cave was shielded by a convenient boulder, hiding the light.

The smoke would give them away in the day, Kostubh thought, even for such a small fire.

“So they’re all dead?”

“Probably,” mused Kostubh. “Or enslaved. The man and his son are dead for sure. I don’t know about the woman and the girl. They didn’t look like slavers to me, though.”

“Should we go back and check? You might be able to get rid of that kid.”

Kostubh frowned, and glanced down at Peanna, who was sleeping next to him. She had spent most of the day in his arms or clinging onto an arm or leg like a burr.

She was old enough to walk around and eat most things, it seemed—at least, she had no trouble eating their dried meat and fruit once he’d chewed it a bit—but she’d not made a sound yet. He figured she must be three or so, just small for her age. She didn’t need diapers—thank goodness!—and should be able to talk.

Was she a mute?

Simply terrified?

She didn’t seem scared of him, at least. She had hung onto him like a leech throughout dinner, which was a thin stew of day-old rabbit, beans, and a few leftover potatoes. He’d chewed the rabbit for her to soften it, and she’d managed a few small pieces, but mostly ate beans and potatoes.

He’d rocked her back and forth until she finally fell asleep.

“No. The mother knew she’d never see her daughter again, and made her choice.”

“So you’re going to raise her!?”

“I have to...” he murmured, half to himself as she smiled in her sleep.

“You don’t know anything about raising a child! And neither do I!”

“True enough, but I can’t just throw her to the wolves, can I?”

He turned back to Robert.

“We can’t go back to Eudoxia, or to Thace, and it looks like the Oasis might not be a good idea if people are getting slaughtered on the road... north, I guess, for now.”

Robert prodded the fire with a stick, watching the sparks fly.

“I wonder if I should go back... to Zeenar, I mean...”

Kostubh shook his head.

“C’mon, Robert, you just got out of a lifetime of humping crates and picking up deino shit. We’re free, free to go where we like, do what we like. You’d be an idiot to throw it all away!”

“But they’re after us! Eudoxia, I mean.”

“Who cares? They’re not gonna chase us, and I don’t care if I never see Eudoxia again. Big world out there, Robert, just waiting for me. Us.”

Peanna stirred, and Kostubh patted her softly back to sleep.

“Stick with me, Robert. There’re some great things coming, you’ll see.”

Robert smiled and let the stick fall into the fire. He stood and brushed the dirt off his tunic.

“I’m with you, Kostubh, wherever you go.”

Kostubh, still seated, reached up to wrist-shake him.

They gradually drifted north along the western edge of the Hills, traveling generally parallel to the trade road but not on it. There was not much traffic, and what little there was showed no interest in a distant pair of riders.

Peanna was still silent but had been crying quietly more often.

She’d been sucking on her fingers more, too... whatever children needed to eat, she wasn’t getting enough of it, realized Kostubh, but what did they eat? They caught some sweetfish, and she obviously liked their soft, white flesh far more than tough rabbit meat.

A few days later they approached Andersweald, a large, isolated stretch of woods along the boundary between mountain and desert. The road cut sharply west here toward the Mohaggers, across the desert, and most travelers spent a day or two here resting up before making the crossing.

There was no clear marker, but gradually the trees thinned and there were scattered fields, sometimes small shacks here and there. The hard-packed dirt road was unchanged, until they turned a corner and saw what awaited.

It was a huge gate, tree trunks roughly hewn into two columns on either side and one across the top horizontally. No guards, no walls, just a tree trunk across the road... and on top of the tree trunk was a row of spikes about half a dozen of which had heads on them.

“I guess they don’t like trespassers,” said Robert.

“No, I heard about this... those are robbers, murderers, and people like them. The heads are up there to tell us to be careful.”

“What do you mean, be careful?”

“Don’t rob or kill anyone, I guess...”

Robert snorted, and they rode on under the row of heads.

There was no water along the nest stage of their planned route, and while it only took two days it was good to be well rested and hydrated before starting. There were a few small homes here in Andersweald, farming and selling food to passing travelers, clumped together around a public well of unknown antiquity.

Kostubh sat Peanna down and let the bucket drop, watching the pulley spin and rattle until the splash sounded. It was a fairly small bucket, and easy to crank back up again.

He spilled the first three buckets into a basin for the horses to drink, and then started filling up their own waterskins. Peanna sat next to him, one arm wrapped around his leg for security, happily splashing one hand in the puddles.

One of the horses swung its head over to investigate, blowing wet mist over her in a loud whuff; she giggled and wiped her face.

“And where’s your mammy, little one?”

Kostubh turned to see a middle-aged woman approaching with a good-sized water keg, obviously to fetch her own water. Dressed in rough-spun wool and leather, she had a square jaw, ice-blue eyes, and twin braids of orange hair hanging down to her massive chest. She set the keg down with a hollow thump and squatted to talk to Peanna up close.

“My, you’re a happy little tyke, aren’t ya?”

She held out her finger and Peanna quickly latched on, pumping it up and down and giggling again.

“This your little girl?”

“Yup. Her name’s Peanna.”

“Where’s her mammy?”

“Dead. I’m all she’s got now.”

“Peanna! What a pretty name! Doesn’t talk much, does she?”

“Nope. She had a big shock when her ma died; still getting over it, I think.”

He squatted down and held his arms open, and Peanna jumped up and into them.

“Seems to like you well enough.”

He stood, carrying her easily in one arm.

“Like I said, I’m all she’s got.”

“You look pretty young to take care of a young ’un,...” she continued.

“No, it’s fine, really, I’m fine...”

She stood up herself and picked up the bucket to draw her own water.

“You just wait right there, young man. This child is starving. You’re coming with me and I’m gonna feed you both, teach you a few things you need to know. This poor child needs a mother.”

Kostubh hesitated. He didn’t want to stay in one place very long if he could help it, not with Eudoxia still nearby, but he knew he was out of his depth.

“I’m Clara,” she said, hinting.

“Um...Kosta. Of Ebnon.”

“Well, Umkosta of Ebnon,” she said, pouring a bucketful into her keg, “you got any baggage other than what’s on them horses?”

“The other horse belongs to my friend, Robe... Robb. Robb of Ebnon.”

Robert was off buying some food and should be back shortly.

“Are you sure it’s alright?” he asked. “We’re fine in the woods.”

“You may be fine, young man, but did you happen to notice Peanna is a little girl? With filthy face, torn tunic, and broken sandal strap? You go get your friend Robb and come see me. That house right over there,” she commanded, pointing to a sod-roofed structure half hidden in the trees. “You get lost just ask for Clara.”

She poured another bucketful into her keg and dropped bucket back in again.

“Ebnon, huh?”

“Yeah.”

“Never been there,” she continued. “Hear it’s all swamp and pirates.”

“Nah, the Boorsh Fens are way west of the city, and the pirates even farther.”